10 Teamwork in Organizations

Teamwork in Organizations

Much of the work that is performed today in organizations requires a focus on teamwork. A team has a specific purpose that it delivers on, has both individual and mutual accountabilities, and often involves shared leadership roles. Teams discuss, make decisions, and perform real work together, and they measure their performance by assessing their collective work products.

Effective teams give companies a significant competitive advantage. In a high-functioning team, the sum is truly greater than the parts. Team members not only benefit from each other’s diverse experiences and perspectives but also stimulate each other’s creativity. In addition, for many people, working in a team can be more fulfilling than working alone.

Several practices have been identified as important contributors to team success, including the following:[1]

Establish urgency, demanding performance standards, and direction. Teams work best when they have a compelling reason for being, and it is thus more likely that the teams will be successful and live up to performance expectations.

Select members for their skill and skill potential, not for their personality. Spend some time up front thinking about the purpose of the project and the anticipated deliverables you will be producing, and think through the specific types of skills you’ll need on the team.

Pay particular attention to first meetings and actions. This is one way of saying that first impressions mean a lot, and it is just as important for teams as for individuals. Keeping an eye on your team’s level of emotional intelligence is very important and will enhance your team’s reputation and ability to navigate future challenges.

Set clear rules of behavior. There is a tendency for teams to rush through ground rules because it feels like they are obvious. However, it is critical that teams take the time up front to capture their own rules of the road in order to keep the team in check. Rules that address areas such as attendance, discussion, confidentiality, project approach, and conflict are key to keeping team members aligned and engaged appropriately.

Set and seize upon a few immediate performance-oriented tasks and goals. What does this mean? Have some quick wins that make the team feel that they’re really accomplishing something and working together well. This is very important to the team’s confidence, as well as just getting into the practices of working as a team. Success in the larger tasks will come soon enough, as the larger tasks are really just a group of smaller tasks that fit together to produce a larger deliverable.

Challenge the team regularly with fresh facts and information. That is, continue to research and gather information to confirm or challenge what you know about your project. Don’t assume that all the facts are static and that you received them at the beginning of the project. Often, you don’t know what you don’t know until you dig in.

Spend time together. Here’s an obvious one that is often overlooked. People are so busy that they forget that an important part of the team process is to spend time together, think together, and bond. Time in person, time on the phone, time in meetings—all of it counts and helps to build camaraderie and trust.

Exploit the power of positive feedback, recognition, and reward. Positive reinforcement is a motivator that will help the members of the team feel more comfortable contributing. It will also reinforce the behaviors and expectations that you’re driving within the team. Although there are many extrinsic rewards that can serve as motivators, a successful team begins to feel that its own success and performance is the most rewarding.

Team Development

If you have been a part of a team, then you have likely intuitively felt that there are different “stages” of team development. A well-known and widely-used model of team development (Figure 10.3 and Video 10.1) suggests that there are four distinct stages of development that help explain the process and complexities of team development: forming, storming, norming, and performing.[2] A fifth stage, adjourning, was later added to explain the disbanding of a team at the end of a project.[3]

Forming

The forming stage begins with the introduction of team members. This is known as the “polite stage” in which the team is mainly focused on similarities and the team looks to the leader for structure and direction. The team members at this point are enthusiastic, and issues are still being discussed on a global, ambiguous level. This is when the informal pecking order begins to develop, but the team is still friendly.

Storming

The storming stage begins as team members begin vying for leadership and testing the team processes. This is known as the “win-lose” stage, as members clash for control of the team and people begin to choose sides. The attitude about the team and the project begins to shift to negative, and there is frustration around goals, tasks, and progress.

Norming

After what can be a very long and painful storming process for the team, the norming stage may slowly start to take root. During norming, the team is starting to work well together, and buy-in to team goals occurs. The team is establishing and maintaining ground rules and boundaries, and there is willingness to share responsibility and control. At this point in the team formation, members begin to value and respect each other and their contributions.

Performing

Finally, as the team builds momentum and starts to get results, it is entering the performing stage. The team is completely self-directed and requires little management direction. The team has confidence, pride, and enthusiasm, and there is a congruence of vision, team, and self. As the team continues to perform, it may even succeed in becoming a high-performing team. High-performing teams have optimized both task and people relationships—they are maximizing performance and team effectiveness.

Watch Video 10.1: The 5 Stages of Team Development to learn about the team development process. Closed captioning is available. Click HERE to read a transcript.

Team Development Process

The process of becoming a high-performing team is not a linear process, and there are factors that may cause a team to regress to an earlier stage of development. When a team member is added to the team, this may change the dynamic enough and be disruptive enough to cause a backwards slide to an earlier stage. Similarly, if a new project task is introduced that causes confusion or anxiety for the team, then this may also cause a backwards slide to an earlier stage of development. In such cases, a team has to re-group and will likely re-storm and re-form before getting back to performing as a team.

Task Interdependence

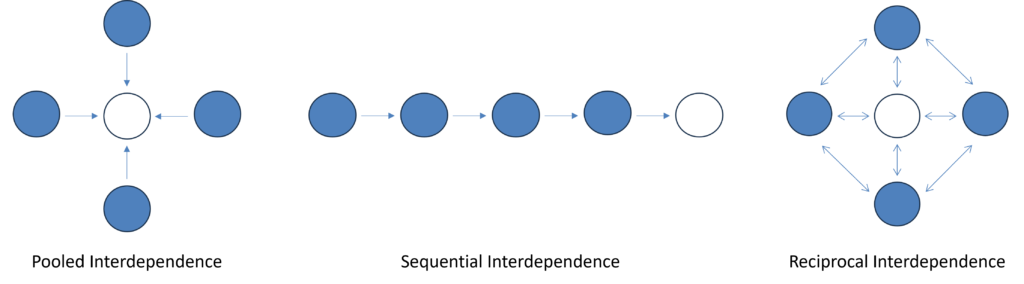

Task interdependence refers to the degree that team members are dependent on one another to get information, support, or materials from other team members to be effective. Interdependence takes three primary forms: pooled, sequential, and reciprocal (Figure 10.4).

-

- Pooled interdependence exists when team members may work independently and simply combine their efforts to create the team’s output. For example, when students divide the section of a research paper and then compile the sections to create one paper, the team is using the pooled interdependence model.

- Sequential interdependence exists when the outputs of one team member becomes the inputs for another. For students using this approach for a research paper, one person may write the introduction of their research paper, then the second person reads what was written by the first person and, drawing from this section, writes about the findings within the paper. Using the findings section, the third person writes the conclusions.

- Reciprocal interdependence occurs when two or more team members depend on one another for inputs. If students use this approach in writing a research paper, they make work together on each phase of the research paper, iterating back and forth among different sections until they complete the paper.

The type of interdependence utilized by teams determines in large part the coordinating mechanisms a team uses, as well as the degree to which team members interact. These are summarized in Table 10.1:

| Type of Interdependence | Coordinating Mechanisms | Degree of Interaction |

| Pooled | Standardization (e.g., specifying criteria for output) | Low |

| Sequential | Planning (e.g., determining the workflow and schedule) | Medium |

| Reciprocal | Mutual adjustment (e.g., adapting to feedback or new information) | High |

Opportunities and Challenges to Team Building

Conflict

There are many sources of conflict for a team, whether due to a communication breakdown, competing views or goals, power struggles, or conflicts between different personalities. The perception is that conflict is generally bad for a team and that it will inevitably bring the team down and cause it to spiral out of control and off track. Conflict does have some potential costs: if conflict is handled poorly, it can create distrust within a team, disrupt team progress and morale, and hinder building lasting relationships.

When managed effectively, however, conflict in teams can encourage a greater diversity of ideas and perspectives and can help people to better understand opposing points of view. It can also enhance a team’s problem-solving capability and can highlight critical points of discussion and contention that need to be given more thought.

There are a variety of individual responses to conflict that you may encounter in your work on teams. Some team members will take the constructive and thoughtful path when conflicts arise, while others may jump immediately to destructive behaviors. To navigate team conflict effectively, the goal is to have a constructive response that encourages dialogue, learning, and resolution.[4] Constructive responses can take both passive and active forms. Passive-constructive responses include thinking, delay responding, and adapting, while active-constructive responses include perspective taking, creating solutions, expressing emotions, and reaching out.

Cohesion

Cohesion can be thought of as a kind of social glue. It refers to the degree of camaraderie within the team. Cohesive teams are those in which members are attached to each other and act as one unit. Generally speaking, the more cohesive a team is, the more productive it will be and the more rewarding the experience will be for the team’s members.[5]

The fundamental factors affecting team cohesion include the following:

- Similarity: the more similar team members are in terms of age, sex, education, skills, attitudes, values, and beliefs, the more likely the team will bond.

- Stability: the longer a team stays together, the more cohesive it becomes.

- Size: smaller team tend to have higher levels of cohesion.

- Support: when team members receive coaching and are encouraged to support their fellow team members, team identity strengthens.

- Satisfaction: cohesion is correlated with how pleased team members are with each other’s performance, behavior, and conformity to team norms.

As you might imagine, there are many benefits to creating a cohesive team. Members are generally more personally satisfied and feel greater self-confidence and self-esteem when in a team where they feel they belong. For many, membership in such a team can be a buffer against stress, which can improve mental and physical well-being. Because members are invested in the team and its work, they are more likely to regularly attend and actively participate in the team, taking more responsibility for the team’s functioning. In addition, members can draw on the strength of the team to persevere through challenging situations that might otherwise be too hard to tackle alone.

Groupthink

When there’s too much conformity, a team may fall victim to groupthink—the tendency to conform to team pressure in making decisions, while failing to think critically or to consider outside influences.[7]

Because members can come to value belonging over all else, an internal pressure to conform may arise, causing some members to modify their behavior to adhere to team norms. Members may become conflict avoidant, focusing more on trying to please each other so as not to be ostracized. In some cases, members might censor themselves to maintain the party line. As such, there is a superficial sense of harmony and less diversity of thought. Having less tolerance for deviants, who threaten the team’s static identity, cohesive teams will often ostracize members who dare to disagree. Members attempting to make a change may even be criticized or undermined by other members, who perceive this as a threat to the status quo. The painful possibility of being marginalized can keep many members in line with the majority.

One way teams can reduce groupthink is by assigning a member to play the devil’s advocate. The job of the devil’s advocate is to point out flawed logic, to challenge the group’s evaluations of various alternatives, and to identify weaknesses in proposed solutions. This pushes the other group members to think more deeply about the advantages and disadvantages of proposed solutions before reaching a decision and implementing it.

Social Loafing

Social loafing refers to the tendency of individuals to put in less effort when working in a team context. This phenomenon, also known as the Ringelmann effect, was first noted by French agricultural engineer Max Ringelmann in 1913. In one study, he had people pull on a rope individually and in teams. He found that as the number of people pulling increased, the team’s total pulling force was less than the individual efforts had been when measured alone.[8]

Why do people work less hard when they are working with other people? Observations show that as the size of a team grows, this effect becomes larger as well.[9] The social loafing tendency is less a matter of being lazy and more a matter of perceiving that one will receive neither one’s fair share of rewards if the team is successful nor blame if the team fails. Rationales for this behavior include, “My own effort will have little effect on the outcome,” “Others aren’t pulling their weight, so why should I?” or “I don’t have much to contribute, but no one will notice anyway.” This is a consistent effect across a great number of team tasks and countries.[10] Research also shows that perceptions of fairness are related to less social loafing.[11] Therefore, teams that are deemed as more fair should also see less social loafing.

Team Diversity

Decision-making and problem-solving can be much more dynamic and successful when performed in a diverse team environment. A 2015 McKinsey report on 366 public companies found that those in the top quartile for ethnic and racial diversity in management were 35% more likely to have financial returns above their industry mean, and those in the top quartile for gender diversity were 15% more likely to have returns above the industry mean.[12] Similarly, a global analysis conducted by Credit Suisse found that organizations with at least one female board member yielded a higher return on equity and higher net income growth than those that did not have any women on the board.[13] Another study by Boston Consulting Group found that diversity in teams is linked to greater innovation.[14]

When individuals are among homogeneous and like-minded teammates, a team is more susceptible to groupthink and may be reticent to think about opposing viewpoints. In a more diverse team with a variety of backgrounds and experiences, opposing viewpoints are more likely to come out and team members are more likely to research and address questions that have been raised. This enables a richer discussion and a more in-depth fact-finding and exploration of opposing ideas and viewpoints in order to solve problems.

Chapter Review

Optional Resources to Learn More

| Books | |

| Ask a Manager: How to Navigate Clueless Colleagues, Lunch-Stealing Bosses, and the Rest of Your Life at Work by Alison Green https://www.askamanager.org/books | |

| Videos | |

| How Do I Say That? Skills to Speak Up When It Matters Most https://youtube.com/playlist?list=PLq6xHLjpckweKfwcqt2Iaj7ysDdHFzHvN | |

| Websites | |

| Student Guide to Group Work https://learningcommons.yorku.ca/groupwork/ | |

| Student Project Toolkit https://learningcommons.yorku.ca/projecttoolkit/ |

Chapter Attribution

This chapter incorporates material from the following sources:

Chapters 2 and 15 of Bright, D. S. & Cortes, A. H. (2019). Principles of management. OpenStax. https://openstax.org/details/books/principles-management. Licensed with CC BY 4.0.

Chapters 9 and 11 of University of Minnesota (2017). Organizational behavior. University of Minnesota Libraries Publishing. https://open.lib.umn.edu/organizationalbehavior/. Licensed with CC BY-NC-SA 4.0.

Chapter 1 of Skripak, S. J. & Poff, R. (2023). Fundamentals of business (4th ed.). VT Publishing. https://pressbooks.lib.vt.edu/fundamentalsofbusiness4e/chapter/chapter-1-teamwork-in-business/. Licensed with CC BY-NC-SA 4.0.

Chapter 9 of Black, J. S. & Bright, D. S. (2019). Organizational behavior. OpenStax. https://openstax.org/books/organizational-behavior/pages/9-4-intergroup-behavior-and-performance. Licensed with CC BY 4.0.

Media Attributions

Figure 10.3: Rice University. OpenStax. https://openstax.org/books/principles-management/pages/15-2-team-development-over-time. Licensed with CC BY-NC-SA 4.0.

Figure 10.5: Hoopes, C. (2023). Types of interdependence. Licensed with CC BY-NC-ND 4.0.

Video 10.1: The Right Questions. (2022, June 19). The 5 stages of team development. [Video]. YouTube. https://youtu.be/-RwkZxGPQb8

- Katzenbach, J. R., & Smith, D. K. (1993). The discipline of teams. Harvard Business Review. ↵

- Tuckman, B. W. (1965). Developmental sequence in small groups. Psychological Bulletin, 63(6), 384–399. ↵

- Tuckman, B. W., & Jensen, M. A. C. (1977). Stages of small-group development revisited. Group & Organization Studies, 2(4), 419-427. ↵

- Capobianco, S., Davis, M. H., & Kraus, L. A. (2004). Managing conflict dynamics: A practical approach. Eckerd College Leadership Development Institute. ↵

- Beal, D. J., Cohen, R. R., Burke, M. J., & McLendon, C. L. (2003). Cohesion and performance in groups: A meta-analytic clarification of construct relations. Journal of Applied Psychology, 88, 989–1004.; Evans, C. R., & Dion, K. L. (1991). Group cohesion and performance: A meta-analysis. Small Group Research, 22, 175–186. ↵

- Schwartz, J., & Wald, M. L. (2003). The nation: NASA's curse? 'Groupthink' is 30 years old, and still going strong. The New York Times. http://www.nytimes.com/2003/03/09/weekinreview/the-nation-nasa-s-curse-groupthink-is-30-years-old-and-still-going-strong.html ↵

- Janis, I. L. (1972). Victims of groupthink. New York: Houghton Mifflin. ↵

- Karau, S. J., & Williams, K. D. (1993). Social loafing: A meta-analytic review and theoretical integration. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 65, 681–706. ↵

- Ibid. ↵

- Gabrenya, W. L., Latane, B., & Wang, Y. (1983). Social loafing in cross-cultural perspective. Journal of Cross-Cultural Perspective, 14, 368–384.; Harkins, S., & Petty, R. E. (1982). Effects of task difficulty and task uniqueness on social loafing. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 43, 1214–1229.; Taylor, D. W., & Faust, W. L. (1952). Twenty questions: Efficiency of problem-solving as a function of the size of the group. Journal of Experimental Psychology, 44, 360–363.; Ziller, R. C. (1957). Four techniques of group decision-making under uncertainty. Journal of Applied Psychology, 41, 384–388. ↵

- Price, K. H., Harrison, D. A., & Gavin, J. H. (2006). Withholding inputs in team contexts: Member composition, interaction processes, evaluation structure, and social loafing. Journal of Applied Psychology, 91, 1375–1384. ↵

- Rock, D., & Grant, H. (2016, November). Why diverse teams are smarter. Harvard Business Review. ↵

- Ibid. ↵

- Lorenzo, R., Voigt, N., Schetelig, K., Zawadzki, A., Welpe, I., & Brosi, P. (2017, April). The mix that matters: Innovation through diversity. Boston Consulting Group. ↵

The capability of individuals to recognize their own emotions and others’ emotions.

Basic rules or principles of conduct that govern a situation or endeavor.

The first stage of team development—the positive and polite stage.

The second stage of team development—when people are pushing against the boundaries.

The third stage of team development—when team resolves its differences and begins making progress.

The fourth stage of team development—when hard work leads to the achievement of the team’s goal.

In teams, the degree that team members are dependent on one another to get information, support, or materials from other team members to be effective.

When team members may work independently and simply combine their efforts to create the team’s output.

Exists when the outputs of one team member becomes the inputs for another.

Occurs when two or more team members depend on one another for inputs.

The degree of camaraderie within a team.

The tendency to conform to team pressure in making decisions, while failing to think critically or to consider outside influences.

The tendency of individuals to put in less effort when working in a group context.

Identity-based differences among and between people that affect their lives as applicants, employees, and customers.