7 Individual Behavior

Many factors influence how individuals behave and interact with others within organizations and in the context of work. Employees and managers are also susceptible to cognitive limitations and biases which can impact how they perceive the world around them, process information, and make decisions. This chapter will introduce you to some of the most common factors that impact individuals in the workplace.

Bounded Rationality

While we might like to think that we can make completely rational decisions, this is often unrealistic given the complex issues faced by employees and managers (Video 7.1). Even when we have gathered seemingly all possible information, we may not be able to make rational sense of all of it, or to accurately forecast or predict the outcomes of our choice.

Bounded rationality is the idea that for complex issues, we cannot be completely rational because we cannot fully grasp all the possible alternatives, nor can we understand all the implications of every possible alternative. Our brains have limitations in terms of the amount of information they can process. Similarly, even when individuals have the cognitive ability to process all the relevant information, they often must make decisions without first having time to collect all the relevant data—their information is incomplete.

Watch Video 7.1: Cognitive Bias. Closed captioning is available. Click HERE to read a transcript.

Escalation of Commitment

Given the lack of complete information, individuals don’t always make the right decision initially, and it may not be clear that a decision was a bad one until after some time has passed. For example, consider a manager who had to choose between two competing software packages that her organization will use on a daily basis to enhance efficiency. She initially chooses the product that was developed by the larger, more well-established company, reasoning that they will have greater financial resources to invest in ensuring that the technology is good. However, after some time it becomes clear that the competing software package is going to be far superior. While the smaller company’s product could be integrated into the organization’s existing systems at little additional expense, the larger company’s product will require a much greater initial investment, as well as substantial ongoing costs for maintaining it. At this point, however, let’s assume that the manager has already paid for the larger company’s (inferior) software. Will she abandon the path that she’s on, accept the loss on the money that’s been invested so far, and switch to the better software? Or will she continue to invest time and money into trying to make the first product work?

Escalation of commitment is the tendency of decision makers to remain committed to poor decisions, even when doing so leads to negative outcomes. Once we commit to a decision, we may find it difficult to reevaluate that decision rationally. It can seem easier to “stay the course” than to admit (or to recognize) that a decision was poor. It’s important to acknowledge that not all decisions are going to be good ones, in spite of our best efforts. Effective employees and managers recognize that progress down the wrong path isn’t really progress, and they are willing to reevaluate decisions and change direction when appropriate.

Personal Biases

Our decision-making is also limited by our own biases. We tend to be more comfortable with ideas, concepts, things, and people that are familiar to us or similar to us. We tend to be less comfortable with that which is unfamiliar, new, and different. One of the most common biases that we have, as humans, is the tendency to like other people who we think are similar to us.[1] While these similarities can be observable (based on demographic characteristics such as race, gender, and age), they can also be a result of shared experiences (such as attending the same university) or shared interests (such as being in a book club together). This similar-to-me bias and preference for the familiar can lead to a variety of problems for managers and organizations: hiring less-qualified applicants because they are similar to the manager in some way, paying more attention to some employees’ opinions and ignoring or discounting others, choosing a familiar technology over a new one that is superior, sticking with a supplier that is known over one that has better quality, and so on.

It can be incredibly difficult to overcome our biases because of the way our brains work. The brain excels at organizing information into categories, and it doesn’t like to expend the effort to re-arrange once the categories are established. As a result, we tend to pay more attention to information that confirms our existing beliefs and less attention to information that is contrary to our beliefs, a shortcoming that is referred to as confirmation bias (Video 7.2).[2]

Watch Video 7.2: Conformation Bias. Closed captioning is available. Click HERE to read a transcript.

In fact, we don’t like our existing beliefs to be challenged. Such challenges feel like a threat, which tends to push our brains towards the reactive system and prevent us from being able to logically process the new information via the reflective system. It is hard to change people’s minds about something if they are already confident in their convictions. So, for example, when a manager hires a new employee who they like and are convinced is going to be excellent, they will tend to pay attention to examples of excellent performance and ignore examples of poor performance (or attribute those events to things outside the employee’s control). The manager will also tend to trust that employee and therefore accept their explanations for poor performance without verifying the truth or accuracy of those statements. The opposite is also true; if we dislike someone, we will pay attention to their negatives and ignore or discount their positives. We are less likely to trust them or believe what they say at face value. This is why politics tend to become very polarized and antagonistic within a two-party system. It can be very difficult to have accurate perceptions of those we like and those we dislike. The effective manager will try to evaluate situations from multiple perspectives and gather multiple opinions to offset this bias when making decisions.

Attribution Theory

A major influence on how people behave is the way they interpret the events around them. People who feel they have control over what happens to them are more likely to accept responsibility for their actions than those who feel control of events is out of their hands. The cognitive process by which people interpret the reasons or causes for their behavior is described by attribution theory.[3] Specifically, “attribution theory concerns the process by which an individual interprets events as being caused by a particular part of a relatively stable environment.”[4]

Attribution theory is based largely on the work of Fritz Heider. Heider argues that behavior is determined by a combination of internal forces (e.g., abilities or effort) and external forces (e.g., task difficulty or luck), as well as that it is perceived determinants, rather than actual ones, that influence behavior. Hence, if employees perceive that their success is a function of their own abilities and efforts, they can be expected to behave differently than they would if they believed job success was due to chance.

The Attribution Process

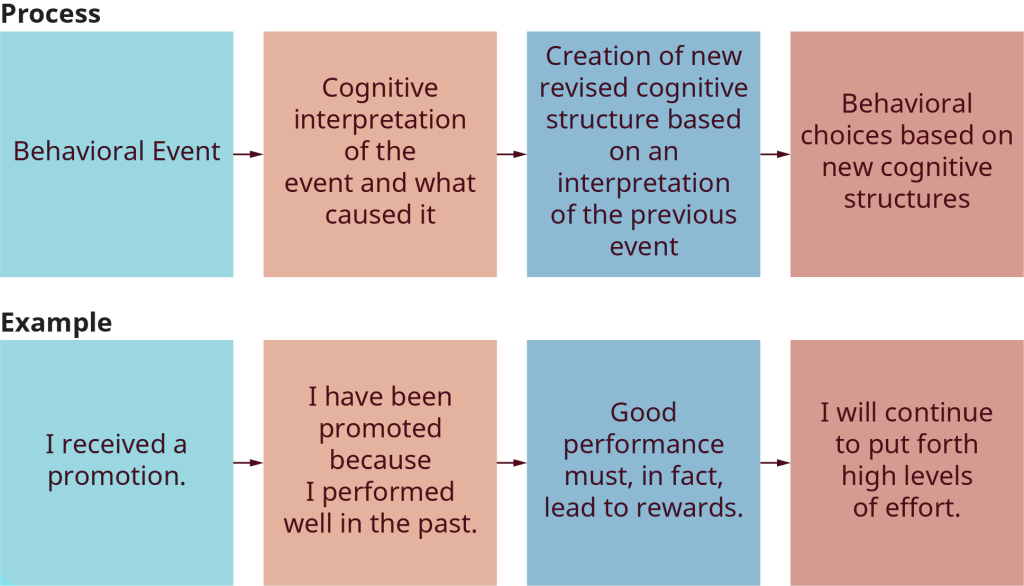

The underlying assumption of attribution theory is that people are motivated to understand their environment and the causes of particular events. If individuals can understand these causes, they will then be in a better position to influence or control the sequence of future events. This process is diagrammed in Figure 7.1.

Specifically, attribution theory suggests that particular behavioral events (e.g., being promoted) are analyzed by individuals to determine their causes. This process may lead to the conclusion that the promotion resulted from the individual’s own effort or, alternatively, from some other cause, such as luck. Based on such cognitive interpretations of events, individuals revise their cognitive structures and rethink their assumptions about causal relationships. For instance, an individual may infer that performance does indeed lead to promotion. Based on this new structure, the individual makes choices about future behavior. In some cases, the individual may decide to continue exerting high levels of effort in the hope that it will lead to further promotions. On the other hand, if an individual concludes that the promotion resulted primarily from chance and was largely unrelated to performance, a different cognitive structure might be created, and there might be little reason to continue exerting high levels of effort. In other words, the way in which we perceive and interpret events around us significantly affects our future behaviors.

Attribution Bias

One final point should be made with respect to the attributional process. In making attributions concerning the causes of behavior, people tend to make certain errors of interpretation. Two such errors, or attribution biases, should be noted here. The first is called the fundamental attribution error (Video 7.3). This error is a tendency, when assessing another person’s actions or behavior, to underestimate the effects of external or situational causes and to overestimate the effects of internal or personal causes. For example, if we observe a major problem within another department, we are more likely to blame people rather than events or situations.

Watch Video 7.3: Fundamental Attribution Error. Closed captioning is available. Click HERE to read a transcript.

The second error in attribution processes is called the self-serving bias (Video 7.4). There is a tendency, not surprisingly, for individuals to attribute success on an event or project to their own actions while attributing failure to others. Hence, we often hear sales representatives saying, “I made the sale,” but “They stole the sale from me” rather than “I lost it.” Considered together, fundamental attribution error and self-serving bias help explain why employees looking at the same event often “see” substantially different things.

Watch Video 7.4: Self-serving Bias. Closed captioning is available. Click HERE to read a transcript.

Stereotypes and Self-Fulfilling Prophecy

A self-fulfilling prophecy is an expectation held by a person that alters their behavior in a way that tends to make it true. For example, when we hold stereotypes about a person, we tend to treat the person according to our expectations. This treatment can influence the person to act according to our stereotypic expectations, thus confirming our stereotypic beliefs. Research by Rosenthal and Jacobson found that disadvantaged students whose teachers expected them to perform well had higher grades than disadvantaged students whose teachers expected them to do poorly.[5]

Consider this example of cause and effect in a self-fulfilling prophecy: If an employer expects a job applicant to be incompetent, the potential employer might treat the applicant negatively during the interview by engaging in less conversation, making little eye contact, and generally behaving coldly toward the applicant.[6] In turn, the job applicant will perceive that the potential employer dislikes him, and he will respond by giving shorter responses to interview questions, making less eye contact, and generally disengaging from the interview. After the interview, the employer will reflect on the applicant’s behavior, which seemed cold and distant, and the employer will conclude, based on the applicant’s poor performance during the interview, that the applicant was in fact incompetent. Do you think this job applicant is likely to be hired?

Another dynamic that can reinforce stereotypes is confirmation bias. When interacting with the target of our prejudice, we tend to pay attention to information that is consistent with our stereotypic expectations and ignore information that is inconsistent with our expectations. Furthermore, we tend to seek out information that supports our stereotypes or pre-existing beliefs and ignore information that is inconsistent with our stereotypes or pre-existing beliefs.[7] In the job interview example, the employer may not have noticed that the job applicant was friendly and engaging, and that he provided competent responses to the interview questions in the beginning of the interview. Instead, the employer focused on the job applicant’s performance in the later part of the interview, after the applicant changed his demeanor and behavior to match the interviewer’s negative treatment.

In-Groups and Out-Groups

We all belong to gender, race, age, and social economic groups. These groups provide a powerful source of identity and self-esteem and serve as our in-groups.[8] An in-group is a group that we identify with or see ourselves as belonging to. A group that we don’t belong to, or an out-group, is a group that we view as fundamentally different from us (Video 7.5). Because we often feel a strong sense of belonging and emotional connection to our in-groups, we develop in-group bias: a preference for our own group over other groups. This in-group bias can result in prejudice and discrimination because the out-group is perceived as different and is less preferred than our in-group.

Watch Video 7.5: In-group/Out-group. Closed captioning is available. Click HERE to read a transcript.

One function of prejudice is to help us feel good about ourselves and maintain a positive self-concept. This need to feel good about ourselves extends to our in-groups: we want to feel good and protect our in-groups. We seek to resolve threats individually and at the in-group level. This often happens by blaming an out-group for the problem. Scapegoating is the act of blaming an out-group when the in-group experiences frustration or is blocked from obtaining a goal.[9]

Despite the group dynamics that seem only to push groups toward conflict, there are forces that promote reconciliation between groups: the expression of empathy, the acknowledgment of past suffering on both sides, and the halt of destructive behaviors.

Job Satisfaction

Some people love their jobs, some people tolerate their jobs, and some people cannot stand their jobs. Job satisfaction describes the degree to which individuals enjoy their job. It was described by Edwin Locke as the state of feeling resulting from appraising one’s job experiences.[10] Job satisfaction is impacted by many different factors associated with the work itself (Table 7.1), as well as our personality and the culture we come from and live in.[11]

Job satisfaction is typically measured after a change in an organization, such as a shift in the management model, to assess how the change affects employees. It may also be routinely measured by an organization to assess one of many factors expected to affect the organization’s performance. In addition, polling companies like Gallup regularly measure job satisfaction on a national scale to gather broad information on the state of the economy and the workforce.[12]

| Factor | Description |

| Autonomy | Individual responsibility, control over decisions |

| Work content | Variety, challenge, role clarity |

| Communication | Feedback |

| Financial rewards | Salary and benefits |

| Growth and development | Personal growth, training, education |

| Promotion | Career advancement opportunity |

| Coworkers | Professional relations or adequacy |

| Supervision and feedback | Support, recognition, fairness |

| Workload | Time pressure, tedium |

| Work demands | Extra work requirements, insecurity of position |

Measures of job satisfaction are somewhat correlated with job performance; in particular, they appear to relate to organizational citizenship or discretionary behaviors on the part of an employee that further the goals of the organization.[16] Job satisfaction is related to general life satisfaction, although there has been limited research on how the two influence each other or whether personality and cultural factors affect both job and general life satisfaction. One carefully controlled study suggested that the relationship is reciprocal: Job satisfaction affects life satisfaction positively, and vice versa.[17] Job satisfaction, specifically low job satisfaction, is also related to withdrawal behaviors, such as leaving a job or absenteeism.[18] The relationship with turnover itself, however, is weak.[19] Finally, it appears that job satisfaction is related to organizational performance, which suggests that implementing organizational changes to improve employee job satisfaction will improve organizational performance.[20]

Chapter Review

Optional Resources to Learn More

| Books | |

| Thinking Fast and Slow by Daniel Kahneman https://us.macmillan.com/books/9780374533557/thinkingfastandslow | |

| Videos | |

| “Hidden Traps in Decision Making” https://youtu.be/gk1kqJMdv2o | |

| Websites | |

| Cognitive Biases (A list of the most relevant biases in behavioral economics) https://thedecisionlab.com/biases | |

| Ethics Defined Glossary https://ethicsunwrapped.utexas.edu/ethics-defined |

|

| APA Dictionary of Psychology https://dictionary.apa.org/ |

Chapter Attribution

This chapter incorporates material from the following sources:

Chapters 3 and 6 of Black, J. S. & Bright, D. S. (2019). Organizational behavior. OpenStax. https://openstax.org/details/books/organizational-behavior. Licensed with CC BY 4.0.

Chapter 12 of Spielman, R. M., Jenkins, W. J., & Lovett, M. D. (2020). Psychology 2e. OpenStax. https://openstax.org/books/psychology-2e/pages/12-introduction. Licensed with CC BY 4.0.

Media Attributions

Figure 7.1: Rice University (2019, June 5). The general attribution process. OpenStax. https://openstax.org/books/organizational-behavior/pages/3-3-attributions-interpreting-the-causes-of-behavior#ch03fig05. Licensed with CC BY-NC-SA 4.0.

Video 7.1: McCombs School of Business (2021, January 28). Cognitive bias [Video]. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=TlOUnOWfw3M

Video 7.2: McCombs School of Business (2021, January 28). Confirmation bias [Video]. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=7zoWTb3KP-k

Video 7.3: McCombs School of Business (2018, December 18). Fundamental attribution error [Video]. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Y8IcYSrcaaA

Video 7.4: McCombs School of Business (2018, December 18). Self-serving bias [Video]. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=NkpXMxt4f3s

Video 7.5: McCombs School of Business (2018, December 18). In-group/out-group [Video]. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=AkYJOYrNiSw

- Aberson, C. L., Healy, M., & Romero, V. (2000). Ingroup bias and self-esteem: A meta-analysis. Personality and Social Psychology Review, 4: 157-173. ↵

- Kolbert, E. (2017, February 27). Why facts don’t change our minds. The New Yorker. ↵

- Kelley, H. H. (1973, February). The process of causal attributions. American Psychologist, 107–128.; Forsterling, F. (1985, November). Attributional retraining: A review. Psychological Bulletin, 495–512.; Weiner, B. (1980). Human motivation. Holt, Rinehart and Winston. ↵

- Heider, F. (1958). The psychology of interpersonal relations. John Wiley & Sons Inc., 297. ↵

- Rosenthal, R., & Jacobson, L. F. (1968). Teacher expectations for the disadvantaged. Scientific American, 218, 19–23. ↵

- Hebl, M. R., Foster, J. B., Mannix, L. M., & Dovidio, J. F. (2002). Formal and interpersonal discrimination: A field study of bias toward homosexual applicants. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 28(6), 815–825. ↵

- Wason, P. C., & Johnson-Laird, P. N. (1972). The psychology of deduction: Structure and content. Harvard University Press. ↵

- Tajfel, H., & Turner, J. C. (1979). An integrative theory of intergroup conflict. In W. G. Austin & S. Worchel (Eds.), The social psychology of intergroup relations, 33–48. Brooks-Cole. ↵

- Allport, G. W. & Odbert, H. S. (1936). Trait-names: A psycho-lexical study. Psychological Review Company. ↵

- Locke, E. A. (1976). The nature and causes of job satisfaction. In M. D. Dunnette (Ed.), Handbook of industrial and organizational psychology, 1297–1349. Rand McNally. ↵

- Saari, L. M., & Judge, T. A. (2004). Employee attitudes and job satisfaction. Human Resource Management, 43, 395–407. ↵

- Saad, L. (2012). U.S. workers least happy with their work stress and pay: Satisfaction is highest for safety conditions and relations with coworkers. Gallup Economy. http://www.gallup.com/poll/158723/workers-least-happy-work-stress-pay.aspx ↵

- Saari, L. M., & Judge, T. A. (2004). Employee attitudes and job satisfaction. Human Resouce Management, 43, 395–407. ↵

- Judge, T. A., Piccolo, R. F., Podsakoff, N. P., Shaw, J. C., & Rich, B. L. (2010). The relationship between pay and job satisfaction: A meta-analysis of the literature. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 77(2), 157–167. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvb.2010.04.002 ↵

- Ibid. ↵

- Judge, T. A., & Kammeyer-Mueller, J. D. (2012). Job attitudes. Annual Review of Psychology, 63, 341–367. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-psych-120710-100511 ↵

- Judge, T. A., & Watanabe, S. (1993). Another look at the job satisfaction-life satisfaction relationship. Journal of Applied Psychology, 78(6), 939–948. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.78.6.939 ↵

- Judge, T. A., & Kammeyer-Mueller, J. D. (2012). Job attitudes. Annual Review of Psychology, 63, 341–367. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-psych-120710-100511 ↵

- Ibid. ↵

- Ibid. ↵

The idea that for complex issues, we cannot be completely rational because we cannot fully grasp all the possible alternatives, nor can we understand all the implications of every possible alternative.

The tendency of decision makers to remain committed to poor decision, even when doing so leads to increasingly negative outcomes.

The tendency to prefer the familiar, specifically people that look and think like us.

The tendency to pay more attention to information that confirms our existing beliefs and less attention to information that is contrary to our beliefs.

The cognitive process by which people interpret the reasons or causes for their behavior.

The tendency to underestimate the effects of external or situational causes of behavior and to overestimate the effects of internal or personal causes.

The tendency for individuals to attribute their successes to their own actions while attributing their failures to others.

An expectation held by a person that alters their behavior in a way that tends to make it true.

A widely held generalization about a group of people. Stereotyping is a process in which attributes are assigned to people solely on the basis of their class or category. It is particularly likely to occur when one meets new people, since very little is known about them at that time.

A group that we identify with or see ourselves as belonging to.

A group that we don’t belong to and that we view as fundamentally different from us.

The degree to which individuals enjoy their job.