8 Motivation

What is Motivation?

People can be a firm’s most important resource. They can also be the most challenging resource to manage well. Employees who are motivated and work hard to achieve personal and organizational goals can become a crucial competitive advantage for a firm. The key then is understanding what motivates individuals, and how an organization can create a workplace that allows people to perform to the best of their abilities.

Motivation is the set of forces that prompt a person to release energy in a certain direction. As such, motivation is essentially a need- and want-satisfying process. A need is best defined as the gap between what is and what is required. Similarly, a want is the gap between what is and what is desired. Unsatisfied needs and wants create a state of tension that motivates individuals to practice behavior that will result in the need being met or the want being fulfilled. That is, motivation is what pushes us to move from where we are to where we want to be, because expending that effort will result in some kind of reward.

Rewards can be divided into two basic categories: intrinsic and extrinsic. Intrinsic rewards come from within the individual—things like satisfaction, contentment, sense of accomplishment, confidence, and pride. By contrast, extrinsic rewards come from outside the individual and include things like pay raises, promotions, bonuses, prestigious assignments, and so forth. Figure 8.1 illustrates the motivation process.

Successful managers are able to marshal the forces to motivate employees to achieve organizational goals. And just as there are many types of gaps between where organizations are and where they want to be, there are many motivational theories from which managers can draw to inspire employees to bridge those gaps.

Expectancy Theory

One of the best-supported and most widely accepted theories of motivation is expectancy theory (Video 8.1), which focuses on the link between motivation and behavior.[1]

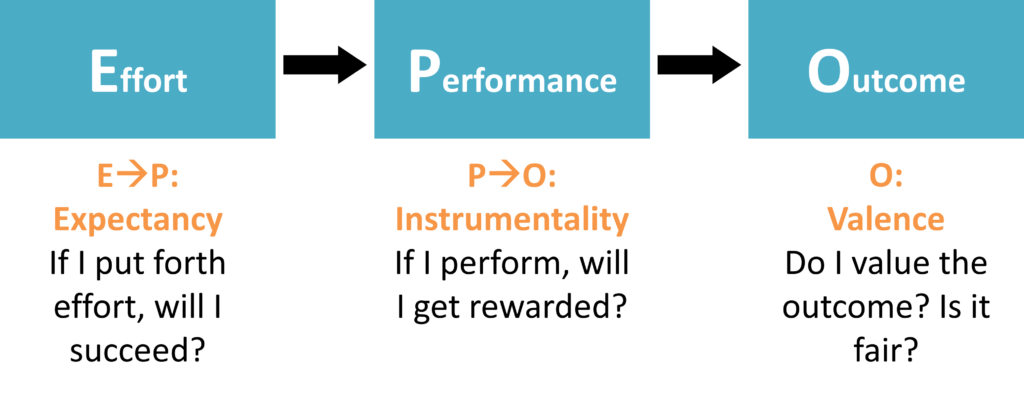

According to expectancy theory, the probability of an individual acting in a particular way depends on the strength of that individual’s belief that the act will have a particular outcome and on whether the individual values that outcome. The degree to which an employee is motivated depends on three important relationships, shown in Figure 8.2.

- The expectancy link, or the link between effort and performance: the strength of the individual’s expectation that a certain amount of effort will lead to a certain level of performance.

- The instrumentality link, or the link between performance and outcome: the strength of the expectation that a certain level of performance will lead to a particular outcome.

- The valence, or outcome: the degree to which the individual expects the anticipated outcome to satisfy personal needs or wants. Some outcomes have more valence, or value, for individuals than others do.

To apply expectancy theory to a real-world situation, let’s analyze an automobile-insurance company with 100 agents who work from a call center. Assume that the firm pays a base salary of $3,000 a month, plus a $300 commission on each policy sold above ten policies a month. In terms of expectancy theory, under what conditions would an agent be motivated to sell more than ten policies a month?

- The agent would have to believe that his or her efforts would result in policy sales (that, in other words, there’s a positive link between effort and performance).

- The agent would have to be confident that if he or she sold more than ten policies in a given month, there would indeed be a bonus (a positive link between performance and reward).

- The bonus per policy—$300—would have to be of value to the agent.

Now let’s alter the scenario slightly. Say that the company raises prices, thus making it harder to sell the policies. How will agents’ motivation be affected? According to expectancy theory, motivation will suffer. Why? Because agents may be less confident that their efforts will lead to satisfactory performance. What if the company introduces a policy whereby agents get bonuses only if buyers don’t cancel policies within 90 days? Now agents may be less confident that they’ll get bonuses even if they do sell more than ten policies. Motivation will decrease because the link between performance and reward has been weakened. Finally, what will happen if bonuses are cut from $300 to $50? Obviously, the reward would be of less value to agents, and, again, motivation will suffer. The message of expectancy theory, then, is fairly clear: managers should offer rewards that employees value, set performance levels that they can reach, and ensure a strong link between performance and reward.

Equity Theory

Another contemporary explanation of motivation, equity theory (Video 8.2), is based on individuals’ perceptions about how fairly they are treated compared with their coworkers.[2]

Equity means justice or fairness, and in the workplace it refers to employees’ perceived fairness of the way they are treated and the rewards they earn. For example, imagine that after graduation you were offered a job that paid $65,000 a year and had great benefits. You’d probably be ecstatic, even more so if you discovered that the coworker in the next cubicle was making $53,000 for the same job. But what if that same colleague were instead making $72,000 for the same job? You’d probably think it unfair, particularly if the coworker had the same qualifications and started at the same time as you did. Your determination of the fairness of the situation would depend on how you felt you compared to the other person, or referent.

Employees evaluate their own outcomes (e.g., salary, benefits) in relation to their inputs (e.g., number of hours worked, education, and training) and then compare the outcomes-to-inputs ratio to one of the following:

- Someone in a similar position

- Someone holding a different position in the same organization

- Someone with a similar occupation

- Someone who shares certain characteristics (such as age, education, or level of experience)

- Oneself at another point in time

When individuals perceive that the ratio of their contributions to rewards is comparable to that of others, they perceive that they’re being treated fairly or equitably; when they perceive that the ratio is out of balance, they perceive inequity. Occasionally, people will perceive that they’re being treated better than others. More often, however, they conclude that others are being treated better (and that they themselves are being treated worse).

What will an employee do if he or she perceives an inequity? The individual might try to bring the ratio into balance, by making one of the following choices:

- Change their work habits (exert less effort on the job)

- Change their job benefits and income (ask for a raise, steal from the employer)

- Distort their perception of themselves (“I always thought I was smart, but now I realize I’m a lot smarter than my coworkers.”)

- Distort their perceptions of others (“Joe’s position is really much less flexible than mine.”)

- Look at the situation from a different perspective (“I don’t make as much as the other department heads, but I make a lot more than most graphic artists.”)

- Leave the situation (quit the job)

Managers can use equity theory to improve worker satisfaction. Knowing that every employee seeks equitable and fair treatment, managers can make an effort to understand an employee’s perceptions of fairness and take steps to reduce concerns about inequity.

Organizational Justice

In recent years, equity theory has been extended into the broader concept of organizational justice, which encompasses three distinct forms of justice (Video 8.3 and Figure 8.3).[3]

Watch Video 8.3: Perceptions of Fairness, Justice and Trust to learn more about organizational justice. Closed captioning is available. Click HERE to read a transcript.

When employees receive rewards (or punishments), they evaluate them in terms of the fairness of the outcome. This is referred to as distributive justice. Employees also assess rewards in terms of how fair the processes used to distribute them are, called procedural justice. For example, during organizational downsizing, when employees lose their jobs, employees may ask whether the loss of work is fair (distributive justice). But they may also assess the fairness of the process used to decide who is laid off (procedural justice). For example, layoffs based on seniority may be perceived as more fair than layoffs based on supervisors’ opinions. Finally, employees also assess whether they are treated with respect and dignity, which reflects a third form of organizational justice, known as interactional justice.

Goal-setting Theory

Goal-setting theory, or simply goal theory, is based on the premise that an individual’s intention to work toward a goal is a primary source of motivation (Video 8.4). In addition, goal theory states that people will perform better if they have difficult, specific, accepted performance goals or objectives.[4]

Watch Video 8.4: Goal Setting Theory. Closed captioning is available. Click HERE to read a transcript.

The first and most basic premise of goal theory is that people will attempt to achieve those goals that they intend to achieve. Thus, if we intend to do something (like get an A on an exam), we will exert effort to accomplish it. Without such goals, our effort at the task (studying) required to achieve the goal is less. Students whose goals are to get As generally study harder than students who don’t have this goal. This doesn’t mean that people without goals are unmotivated. It simply means that people with goals are more motivated. The intensity of their motivation is greater, and they are more directed.

The second basic premise is that difficult goals result in better performance than easy goals. This does not mean that difficult goals are always achieved, but our performance will usually be better when we intend to achieve harder goals. Your goal of an A in your economics course may not get you your A, but it may earn you a B+, which you wouldn’t have gotten otherwise. Difficult goals cause us to exert more effort, and this almost always results in better performance.

Another premise of goal theory is that specific goals are better than vague goals. We often wonder what we need to do to be successful. Have you ever asked a professor “What do I need to do to get an A in this course?” If she responded “Do well on the exams,” you weren’t much better off for having asked. This is a vague response. Goal theory says that we perform better when we have specific goals. Had your professor told you to turn in all the problem sets, to pay close attention to the essay questions on exams, and to aim for scores in the 90s, you would have something concrete on which to build a strategy.

A key premise of goal theory is that people must accept the goal. Usually we set our own goals. But sometimes others set goals for us. Your professor telling you your goal is to “score at least a 90 percent on your exams” doesn’t mean that you’ll accept this goal. Maybe you don’t feel you can achieve scores in the 90s. Or, you’ve heard that 90 isn’t good enough for an A in the course. This happens in work organizations quite often. Supervisors give orders that something must be done by a certain time. The employees may fully understand what is wanted, yet if they feel the order is unreasonable or impossible, they may not exert much effort to accomplish it. Thus, it is important for people to accept the goal. They need to feel that it is also their goal. If they do not, goal theory predicts that they won’t try as hard to achieve it.

Goal theory also states that people need to commit to a goal in addition to accepting it. Goal commitment is the degree to which we dedicate ourselves to achieving a goal. Goal commitment is about setting priorities. We can accept many goals (go to all classes, stay awake during classes, take lecture notes), but we often end up doing only some of them. In other words, some goals are more important than others. And we exert more effort for certain goals. This also happens frequently at work. A software analyst’s major goal may be to write a new program. Her minor goal may be to maintain previously written programs. It is minor because maintaining old programs is boring, while writing new ones is fun. Goal theory predicts that her commitment, and thus her intensity, to the major goal will be greater.

Allowing people to participate in the goal-setting process often results in higher goal commitment. This has to do with ownership. And when people participate in the process, they tend to incorporate factors they think will make the goal more interesting, challenging, and attainable. Thus, it is advisable to allow people some input into the goal-setting process. Imposing goals on them from the outside usually results in less commitment (and acceptance).

Drawbacks of Goal-setting Theory

Goal theory can be a tremendous motivational tool, but several cautions are appropriate. First, setting goals in one area can lead people to neglect other areas. Second, goal setting sometimes has unintended consequences. For example, employees set easy goals so that they look good when they achieve them. Or it causes unhealthy competition between employees. Or an employee sabotages the work of others so that only she has goal achievement.

Some managers use goal setting in unethical ways. They may manipulate employees by setting impossible goals. This enables them to criticize employees even when the employees are doing superior work and, of course, causes much stress. Goal setting should never be abused. Perhaps the key caution about goal setting is that it often results in too much focus on quantified measures of performance. Qualitative aspects of a job or task may be neglected because they aren’t easily measured. Managers must keep employees focused on the qualitative aspects of their jobs as well as the quantitative ones. Finally, setting individual goals in a teamwork environment can be counterproductive.[5] Where possible, it is preferable to have group goals in situations where employees depend on one another in the performance of their jobs.

Reinforcement Theory

Reinforcement theory says that behavior is a function of its consequences (Video 8.5). In other words, people do things because they know other things will follow. So, depending on what type of consequence follows, people will either practice a behavior or refrain from it.

Watch Video 8.5: Reinforcement Theory. Closed captioning is available. Click HERE to read a transcript.

There are three basic types of consequences: positive, negative, and none. In general, we think of positive consequences as rewards, but a reward is anything that increases the particular behavior. In contrast, punishment is anything that decreases the behavior.

Motivating with the reinforcement theory can be tricky because consequences can operate differently for different people and in different situations. What is considered a punishment by one person may, in fact, be a reward for another. Nonetheless, managers can successfully use reinforcement theory to motivate workers to practice certain behaviors and avoid others. Often, managers use both rewards and punishment to achieve the desired results.

Reinforcement occurs when a consequence makes it more likely the response/behavior will be repeated in the future. There are two primary ways to make a response more likely to recur: positive reinforcement and negative reinforcement. In addition, there are two ways to make a response less likely to recur: punishment and extinction.

Making a Behavior More Likely

According to reinforcement theorists, managers can encourage employees to repeat a behavior if they provide a desirable consequence, or reward, after the behavior is performed. A positive reinforcement is a desirable consequence that satisfies an active need or that removes a barrier to need satisfaction (Figure 8.4). It can be as simple as a kind word or as major as a promotion. Companies that provide awards to employees who go the extra mile are utilizing positive reinforcement. It is important to note that there are wide variations in what people consider to be a positive reinforcer. Praise from a supervisor may be a powerful reinforcer for some workers, but not others.

Another technique for making a desired response more likely to be repeated is known as negative reinforcement. When a behavior causes something undesirable to be taken away, the behavior is more likely to be repeated in the future. Managers use negative reinforcement when they remove something unpleasant from an employee’s work environment in the hope that this will encourage the desired behavior. For example, consider a scenario in which an employee doesn’t like being continually reminded by his supervisor to work faster, so he works faster at stocking shelves to avoid being criticized.

Approach using negative reinforcement with extreme caution. Negative reinforcement is often confused with punishment. Punishment, unlike reinforcement (negative or positive), is intended to make a particular behavior go away (not be repeated). Negative reinforcement, like positive reinforcement, is intended to make a behavior more likely to be repeated in the future. In the previous example, the supervisor’s reminders simultaneously punished one behavior (slow stocking) and reinforced another (faster stocking). The difference is often a fine one, but it becomes clearer when we identify the behaviors we are trying to encourage (reinforcement) or discourage (punishment).

Making a Behavior Less Likely

At times it is necessary to discourage a worker from repeating an undesirable behavior. The techniques managers use to make a behavior less likely to occur involve doing something that frustrates the individual’s need satisfaction or that removes a currently satisfying circumstance.

Punishment is an aversive consequence that follows a behavior and makes it less likely to reoccur. Although punishment effectively tells a person what not to do and stops the undesired behavior, it does not, by itself, tell them what they should do. In addition, even when punishment works as intended, the worker being punished often develops negative feelings toward the person who does the punishing.

Finally, the principle of extinction suggests that undesired behavior will decline as a result of a lack of positive reinforcement. If a perpetually tardy employee consistently fails to receive supervisory praise and is not recommended for a pay raise, we would expect this nonreinforcement to lead to an “extinction” of the tardiness. The employee may realize, albeit subtly, that being late is not leading to desired outcomes, and she may try coming to work on time.

Recognition and Empowerment

All employees have unique needs that they seek to fulfill through their jobs. Organizations must devise a wide array of incentives to ensure that a broad spectrum of employee needs can be addressed in the work environment, thus increasing the likelihood of motivated employees.

Formal recognition of superior effort by individuals or groups in the workplace is one way to enhance employee motivation. Recognition serves as positive feedback and reinforcement, letting employees know what they have done well and that their contribution is valued by the organization. Recognition can take many forms, both formal and informal. Some companies use formal awards ceremonies to acknowledge and celebrate their employees’ accomplishments. Others take advantage of informal interaction to congratulate employees on a job well done and offer encouragement for the future. Recognition can take the form of a monetary reward, a day off, a congratulatory e-mail, or a verbal “pat on the back.”

Employee empowerment, sometimes called employee involvement or participative management, involves delegating decision-making authority to employees at all levels of the organization, trusting employees to make the right decision. Employees are given greater responsibility for planning, implementing, and evaluating the results of decisions. Empowerment is based on the premise that human resources, especially at lower levels in the firm, are an underutilized asset. Employees are capable of contributing much more of their skills and abilities to organizational success if they are allowed to participate in the decision-making process and are given access to the resources needed to implement their decisions.

Chapter Review

Optional Resources to Learn More

| Videos | |

| “Purpose—Why We Do What We Do” https://youtu.be/_p4esMj2EC8 | |

| “The Explainer: One More Time, How Do You Motivate Employees?” https://hbr.org/video/5487440968001/the-explainer-one-more-time-how-do-you-motivate-employees |

Chapter Attribution

This chapter incorporates material from the following sources:

Chapter 9 of Gitman, L. J., McDaniel, C., Shah, A., Reece, M., Koffel, L., Talsma, B., & Hyatt, J. C. (2018). Introduction to business. OpenStax. https://openstax.org/books/introduction-business/pages/9-introduction. Licensed with CC BY 4.0.

Chapter 11 of Skripak, S. J. & Poff, R. (2023). Fundamentals of business (4th ed.). VT Publishing. https://pressbooks.lib.vt.edu/fundamentalsofbusiness4e/chapter/chapter-11-motivating-employees/. Licensed with CC BY-NC-SA 4.0.

Chapter 7 of Black, J. S. & Bright, D. S. (2019). Organizational behavior. OpenStax. https://openstax.org/books/organizational-behavior/pages/7-introduction. Licensed with CC BY 4.0.

Media Attributions

Figure 8.1: Rice University. OpenStax. https://openstax.org/books/introduction-business/pages/9-1-early-theories-of-motivation. Licensed with CC BY 4.0.

Figure 8.2: Hoopes, C. (2023). Expectancy theory. Licensed with CC BY-NC-ND 4.0.

Figure 8.3: Hoopes, C. (2023). Organizational justice. Licensed with CC BY-NC-ND 4.0.

Figure 8.4: Hoopes, C. (2023). Reinforcement theory. Licensed with CC BY-NC-ND 4.0.

Video 8.1: GreggU. (2019, June 13). Expectancy theory. [Video]. YouTube. https://youtu.be/DjIlQzYheH0

Video 8.2: GreggU. (2019, June 13). Equity theory. [Video]. YouTube. https://youtu.be/uQutP57MTGg

Video 8.3: GreggU. (2018, November 3). Perceptions of fairness, judgment and trust. [Video]. YouTube. https://youtu.be/U4m5jxF0XHA

Video 8.4: GreggU. (2019, June 14). Goal setting theory. [Video]. YouTube. https://youtu.be/15FXwQGFQhM

Video 8.5: GreggU. (2022, August 31). Reinforcement theory. [Video]. YouTube. https://youtu.be/0fLRyVNax9U

- Vroom, V.H. (1964). Work and motivation. Wiley. ↵

- Adams, J. S. (1963). Towards an understanding of inequity. The Journal of Abnormal and Social Psychology, 67(5), 422–436. https://doi.org/10.1037/h0040968; Pritchard, R. D. (1969). Equity theory: A review and critique. Organizational Behavior & Human Performance, 4(2), 176–211. https://doi.org/10.1016/0030-5073(69)90005-1 ↵

- Greenberg, J. (1987). A taxonomy of organizational justice theories. Academy of Management review, 12(1), 9-22.; Greenberg, J., & Colquitt, J. A. (Eds.). (2013). Handbook of organizational justice. Psychology Press. ↵

- Latham, G. P. & Locke, E. A. (1984). Goal setting: A motivational technique that works! Prentice Hall. ↵

- Mitchell, T. R. & Silver, W. S. (1990). Individual and group goals when workers are interdependent: Effects on task strategies and performance. Journal of Applied Psychology 75, 185–193. ↵

The set of forces that prompt a person to release energy, or exert effort, in a certain direction.

The gap between what is and what is required.

The gap between what is and what is desired.

Rewards that come from within the individual—things like satisfaction, contentment, sense of accomplishment, confidence, and pride.

Rewards that come from outside the individual—things like pay raises, promotions, bonuses, and prestigious assignments.

A theory of motivation that holds that the probability of an individual acting in a particular way depends on the strength of that individual’s belief that the act will have a particular outcome and on whether the individual values that outcome.

In expectancy theory, the link between effort and performance, which refers to the strength of the individual’s expectation that a certain amount of effort will lead to a certain level of performance.

In expectancy theory, the link between performance and outcome, which refers to the strength of the expectation that a certain level of performance will lead to a particular outcome.

In expectancy theory, the outcome, which refers to the degree to which the individual expects the anticipated outcome to satisfy personal needs or wants. Some outcomes have more valence, or value, for individuals than others do.

A theory of motivation that holds that worker satisfaction is influenced by employees’ perceptions about how fairly they are treated compared with their coworkers.

Another person, used for comparison purposes.

Employee perceptions of fairness in the workplace, encompassing three distinct forms of justice: distributive (fair outcomes), procedural (fair process), and interactional (the manner in which a person is treated).

One type of organizational justice, which refers to the perceived fairness of outcomes.

One type of organizational justice, which refers to the fairness of the process used to determine outcomes.

One type of organizational justice, which refers to the manner in which an employee is treated.

A theory of motivation based on the premise that an individual’s intention to work toward a goal is a primary source of motivation.

A theory of motivation that holds that people do things because they know that certain consequences will follow.

Anything that increases a specific behavior.

Anything that decreases a specific behavior.

A desirable consequence that satisfies an active need or that removes a barrier to need satisfaction.

Removing an undesirable consequence to encourage desired behavior.

The principle that suggests that undesired behavior will decline as a result of a lack of positive reinforcement.

In individuals, autonomy and discretion to make their own decisions, as well as control over the resources needed to implement those decisions.