Introduction to Open Educational Resources

Learning Objectives

By the end of this chapter, you will be able to:

- Provide a definition of open educational resources.

- Explain the difference between OER and other free educational materials.

- Describe the challenges and benefits of using OER in a class.

The purpose of this text is to get you involved in the adoption, creation, and use of open educational resources (OER). In this chapter, we will introduce you to the concept of OER and the benefits and challenges of using them.

Optional Watch:

Meet Robin DeRosa, one of the leaders in the Open movement as she shares a bit about the benefits of OER. (run time: 7:22)

Note: The video sound is a bit uneven due to how it was filmed.

Attribution: “Intro to Open Education” by Robin DeRosa is licensed under a CC BY license.

Background

The open education movement was originally inspired by the open source community, with a focus on broadening access to information through the use of free, open content. As Bliss and Smith explain in their breakdown of the history of open education:

“much of our attention focused on OER’s usefulness at providing knowledge in its original form to those who otherwise might not have access. The implicit goal was to equalize access to disadvantaged and advantaged peoples of the world – in MIT’s language, to create ‘a shared intellectual Common.’”[1]

Following the rise of open education in the early 2000s, growing interest in MOOCs, open courseware, and particularly open textbooks catapulted the movement to new heights; however, there are still many instructors who have never heard of open educational resources (OER) today.[2]

What is an OER?

Open educational resources (OER) are openly-licensed, freely available educational materials that can be modified and redistributed by users. They can include any type of educational resource, from syllabi, lessons, modules, videos, software, textbooks, and full courses.

- Openly-licensed: You can read about this more in the Copyright & Licensing chapter.

- Freely Available: The resources must be freely available online with no fee to access. Physical OER may be sold at a low cost to facilitate printing.

- Modifiable: The resource must be made available under an open license that allows for editing. Ideally, it should also be available in an editable format.[3]

The most comprehensive definition of OER available today is provided by the Hewlett Foundation:

“Open Educational Resources are teaching, learning and research materials in any medium – digital or otherwise – that reside in the public domain or have been released under an open license that permits no-cost access, use, adaptation and redistribution by others with no or limited restrictions.”[4]

With a definition so broad that it includes any educational material so long as it is free to access and open, it might be easier to ask, “What isn’t an OER?”

The 5 Rs of Using OER

The terms “open content” and “open educational resources” describe any copyrightable work (traditionally excluding software, which is described by other terms like “open source”) that is either (1) in the public domain or (2) licensed in a manner that provides everyone with free and perpetual permission to engage in the 5R activities:

- RETAIN – make, own, and control a copy of the resource (e.g., download and keep your own copy)

- REVISE – edit, adapt, and modify your copy of the resource (e.g., translate into another language)

- REMIX – combine your original or revised copy of the resource with other existing material to create something new (e.g., make a mashup)

- REUSE – use your original, revised, or remixed copy of the resource publicly (e.g., on a website, in a presentation, in a class)

- REDISTRIBUTE – share copies of your original, revised, or remixed copy of the resource with others (e.g., post a copy online or give one to a friend)

What is Not an OER?

If a resource is not free or openly licensed, it cannot be described as an OER. For example, most materials accessed through your library’s subscriptions cannot be altered, remixed, or redistributed. These materials require special permission to use and therefore cannot be considered “open.” Table 1 below explains the difference between OER and other resources often misattributed as OER.

| Material Type | Openly Licensed | Freely Available | Modifiable |

| Open educational resources | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Free online resources under all rights reserved copyright | No | Yes | No |

| Materials available through the University Library | No | Yes | No |

| Open access articles and monographs | Yes | Yes | Maybe |

| Inclusive access materials* | No | No | No |

Note: Although some materials are free to access for a library’s users, that does not mean that they are free to access for everyone (including the library). Similarly, while some open access resources are made available under a copyright license that enables modification, this is not always the case.

* A note about inclusive access: While we will not dive into a deep discussion of inclusive access, we encourage you to learn the facts by visiting InclusiveAccess.org. It is important to note that inclusive access is NOT OER.

Benefits of Using OER

Benefits for Students

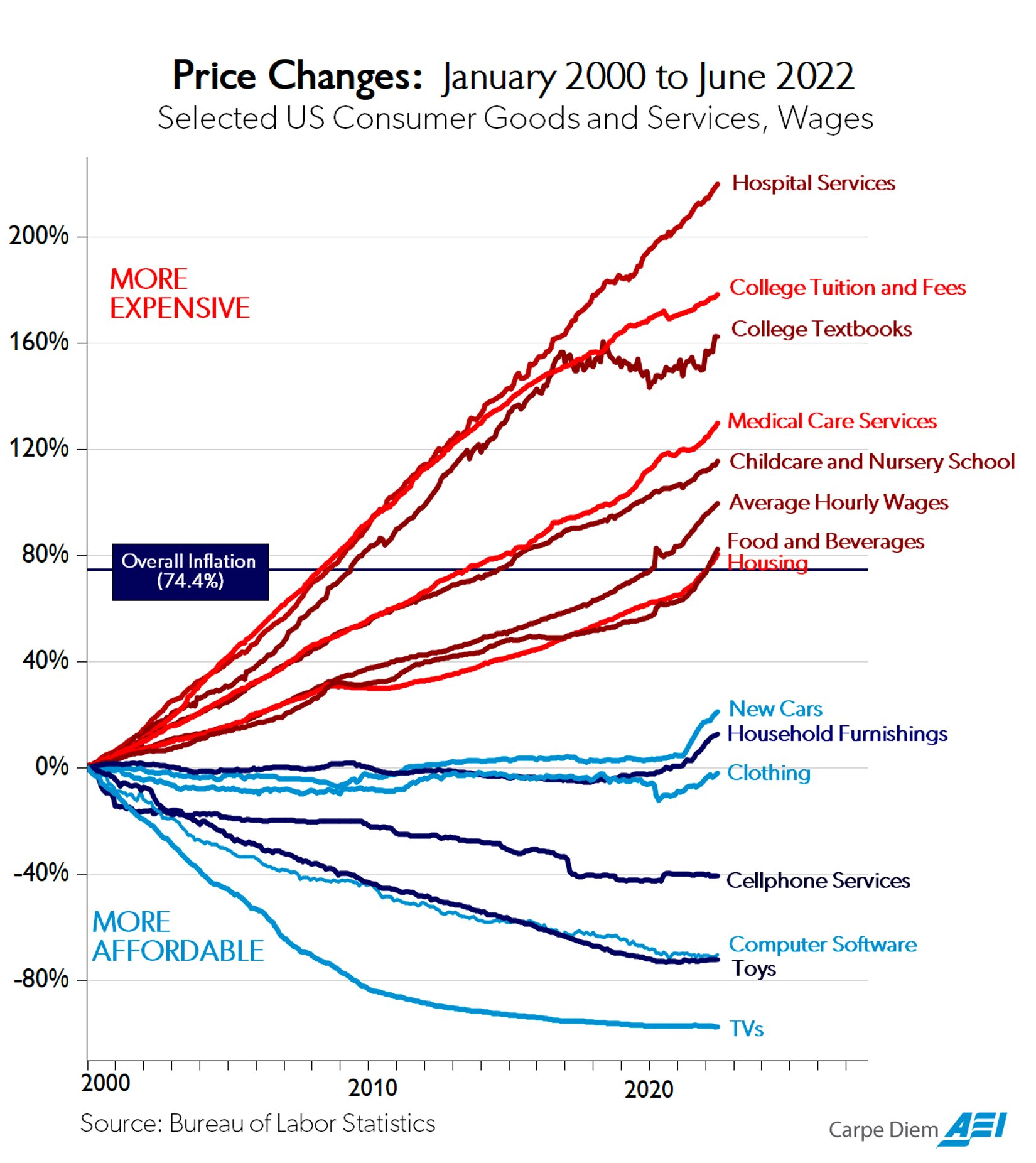

One of the first aspects of OER to be praised by the general public was the cost savings that they could bring to students. As Figure 1 shows, the price of college textbooks has risen greatly over the past 35 years, outpacing all other consumer goods in the Consumer Price Index by a great margin.

The cost of textbooks has a profound impact on college students, many of whom must wait to purchase their course materials until well into the semester or choose not to purchase them at all.[5]

The cost of textbooks might not be a major issue on its own, but it can be an insurmountable hurdle for students already struggling to get by. The problem of food and housing insecurity among college students cannot be fixed by adjusting the price of textbooks alone. There are a wide variety of reasons why these problems are in place.[6] However, the unexpected additional cost of textbooks can make the difference between a student persisting in college or dropping out.

In 2021, the Virginia Academic Library Consortium (VIVA) “conducted a Course Materials Survey for Virginia students in higher education. The survey, approved by the George Mason University IRB as 1735732, built on the work of previous states and regions and included a special emphasis on educational equity. More than 5,600 valid student responses from 41 institutions were received, reflecting an overall response rate of 10%.”[7]

The overarching research questions were

- What is the impact of course material costs on educational equity among Virginia students?

- What course content materials do students find to be most beneficial to their learning?

We’ll discuss some of the findings in our Learning Community; however, consider the following statements from UVA students in response to an open question about their perception of their textbook costs.

“I have often had to purchase a book to share with other students in my class, which was inconvenient at times and required extra planning, but [it] was the only financially viable option.”

“If there are courses where I know the professor will require us to purchase a lot of books, I avoid taking those courses.”

“…too poor to afford them.”

“It has stressed me to the point where I have to choose between groceries and buying the book that month.”

“It’s another limiting factor for those from disadvantaged backgrounds.”

If you’re interested in learning more, you can read the Executive Summary of the study.

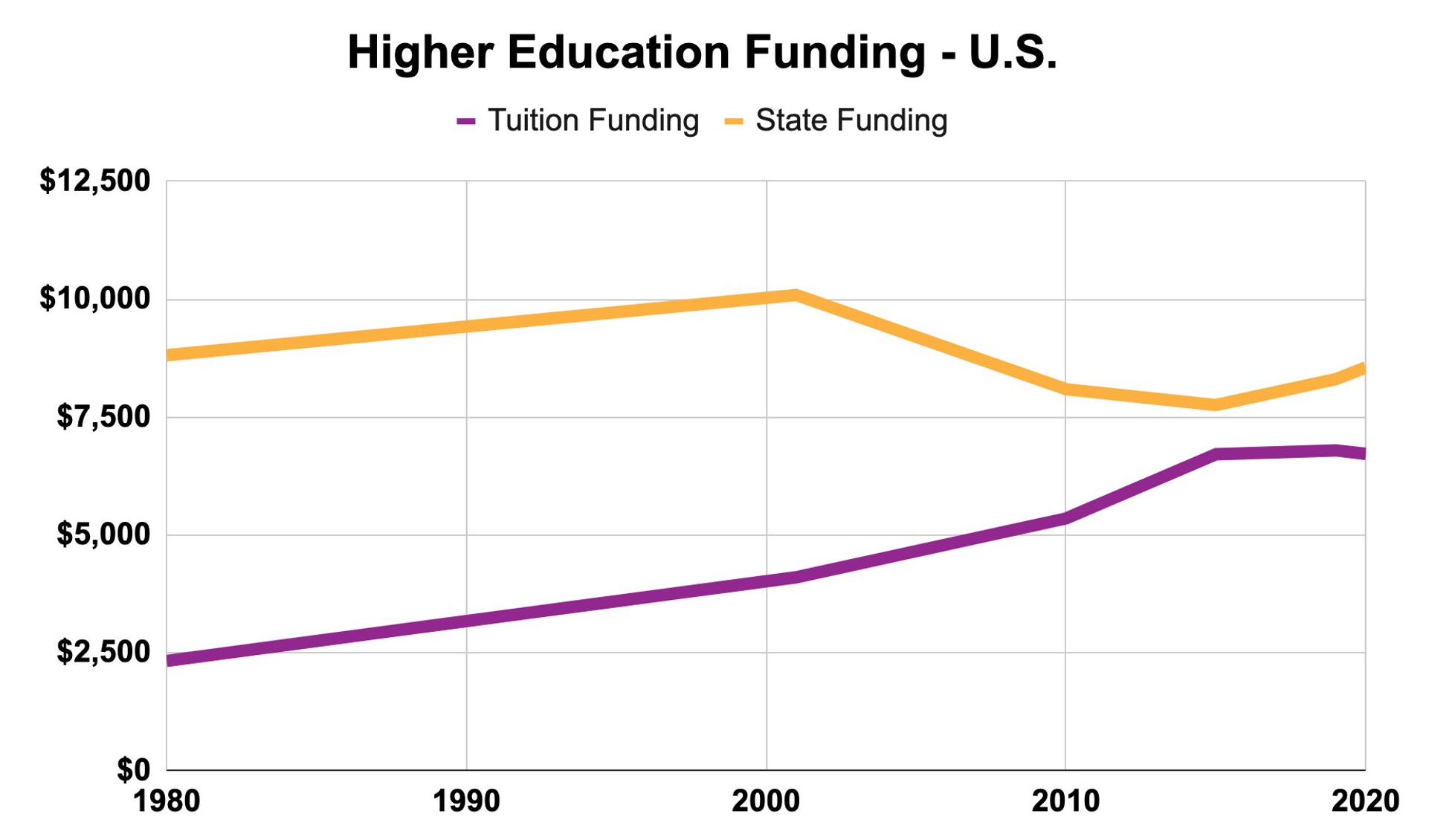

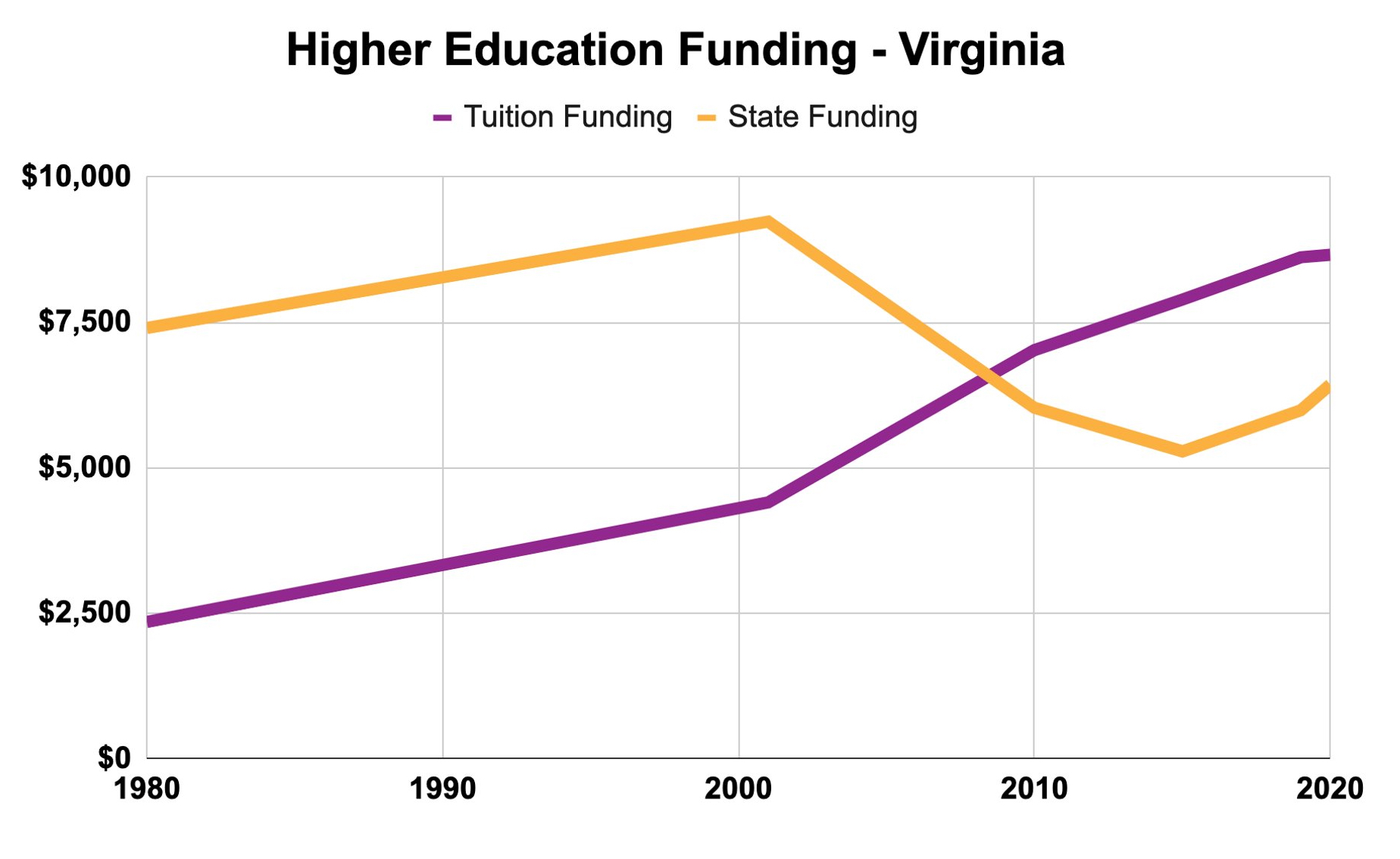

Troubling, the cost of higher education funding continues to shift from the state to the student as visualized in the following charts reflecting data from the State Higher Education Executive Officers Association (SHEEO).

Access to a Quality Education

When you choose to share course materials openly, you are providing students with the opportunity to engage with your content before, during, and after your course. Because OER are always free to access online, students who are interested in taking a course you teach can read up on the course ahead of time and ensure that they are ready and interested in the material. Moreover, students who have already taken your course can be safe in the knowledge that their course materials will not evaporate at the end of the semester and that they can continue to review the materials you provided to them for years to come.

The students who benefit from access to OER are not just the ones in your classroom. Unlike affordability initiatives like course reserves, OER are free for anyone in the world to access, whether they have a college affiliation or not.[8] This encourages aging learners and students in the Global South to explore educational content without having to commit the time and money they might not have to attend college.[9]

Impact on Academic Success

When students have access to course materials from the first day of the semester, the potential for academic success increases. A large-scale study looking at the impact of OER in higher education found that courses with OER adoption had higher final grades and lower rates of DFW (D, F, and Withdrawal grades) for all students. The increase in final grades and lower rates of DFW were even more significant for Pell recipient students, part-time students, and populations historically underserved by higher education.[10]

Benefits for Instructors

Although cost savings are a major talking point in favor of adopting open educational resources, instructors can utilize OER effectively without replacing paid resources at all.[11] In fact, the freedom to adapt OER to instructional needs is often the most attractive aspect of OER. Since OER are openly licensed, educators are free to edit, reorder, and remix OER materials in many ways.

Use, Improve, and Share

- Adapt and revise resources that have already been created to fit your course syllabus.

- Create an updated second edition of an existing OER.

- Tailor resources to fit your specific course context (e.g., translation, local examples).

Network and Collaborate with Peers

- Access educational resources that have been peer-reviewed by experts in your field.

- Create a new open educational resource with a team of your peers.

- Explore user reviews for a more in-depth understanding of the resources available.

Lower Costs to Improve Access to Information

- Enable all students to have equal access to your course materials.

- Provide students with the opportunity to explore course content before enrolling.

In the Teaching in Higher Ed podcast below, Dr. John Stewart, Assistant Director for the Office of Digital Learning at the University of Oklahoma, talks about his experience with OER.

Challenges of Using OER

There are many benefits to using OER in the classroom; however, there are also some drawbacks. The biggest challenge that instructors face when adopting OER is best encapsulated by the phrase “availability may vary.”

Subject Availability

Many of the largest OER projects funded over the past fifteen years targeted high cost, high impact courses to save students money. Because of this, most of the OER available today are for general education courses such as Psychology, Biology, and Calculus.

This does not mean that there are no OER available for specialized subject areas or graduate-level courses; however, there are more resources to choose from for instructors who teach Introduction to Psychology than for those who teach Electronic Systems Integration for Agricultural Machinery & Production Systems.

Note: This is beginning to change as more institutions begin publishing OER through regional and institutional grant programs.

Format & Material Type Availability

As with subject availability, the format and types of OER that have been developed over time have largely been targeted at high enrollment courses which could see substantial cost savings for students. There are many open textbooks available today, but fewer options for ancillary materials. You can find lecture slides, notes, and lesson plans online, but ancillary content such as homework software and test banks are harder to find.[12]

Time & Support Availability

Although the other challenges to OER use are inherent to the resources themselves, this final drawback is a concern for you as a user and creator. It takes time and effort to find OER that might work for your course, and if you want to create and publish new resources, that takes exponentially more time. A good starting point is using an existing OER and discovering what you like/dislike.

Time constraints are always going to be an issue for instructors who want to try something new in their course. Luckily, there are resources available to help you locate, adopt, and implement OER. Contact your local OER expert on campus–that would include both Emily and Bethany–or your subject librarian if you need support.

Check Your Knowledge

Resources for Further Learning

Let’s Reflect

- What, if any, of your current materials might be switched to an OER?

- What aspects of Open resonate most with you and your teaching or learning style?

Let’s Reflect

- Bliss, T.J. and Smith, M. "A Brief History of Open Educational Resources." In Open: The Philosophy and Practices that are Revolutionizing Education and Science, edited by Rajiv Jhangiani and Robert Biswas-Diener, 9-27. London: Ubiquity Press, 2017. DOI: https://doi.org/10.5334/bbc.b. ↵

- Weller, Martin. The Battle for Open: How Openness Won and Why it Doesn't Feel Like Victory. London: Ubiquity Press, 2014. DOI: https://doi.org/10.5334/bam ↵

- Although all OER are openly licensed, many are released in formats that do not easily allow for adaptation. ↵

- William & Flora Hewlett Foundation. "Open Educational Resources." Accessed June 15, 2019. https://hewlett.org/strategy/open-educational-resources/ ↵

- Florida Virtual Campus. 2018 Student Textbook and Course Materials Survey: Executive Summary, 2018. Accessed June 15, 2019. https://www.flbog.edu/documents_meetings/0290_1174_8926_6.3.2%2003a_FLVC_SurveyEXSUM.pdf ↵

- Goldrick-Rab, Sara and Cady, Clare. Supporting Community College Completion with a Culture of Caring: A Case Study of Amarillo College, 2018. https://hope4college.com/supporting-community-college-completion-with-a-culture-of-caring-a-case-study-of-amarillo-college/ ↵

- https://vivalib.org/va/open/survey ↵

- Although OER are free for anyone to access, this access is still limited by who has access to the Internet. Still, since OER can be freely redistributed, some individuals have printed OER for dissemination in areas that do not have Internet access as well. ↵

- Hodgkinson-Williams, Cheryl and Arinto, Patricia B. Adoption and Impact of OER in the Global South. Cape Town & Ottawa: African Minds, International Development Research Centre & Research on Open Educational Resources, 2017. DOI: 10.5281/zenodo.1005330 ↵

- Colvard, Nicholas B., C. Edward Watson, and Hyojin Park. "The impact of open educational resources on various student success metrics." International Journal of Teaching and Learning in Higher Education 30.2 (2018): 262-276. ↵

- Attribution: The Benefits for Instructors section of this chapter was adapted from the SUNY OER Community Course, licensed CC BY 4.0. ↵

- Open textbooks have not always been the most common content shared or marketed as OER. One of the first OER projects, MIT OpenCourseWare, started offering lecture notes, syllabi, and other instructional content openly in 2001. ↵

Free educational materials that are openly licensed to enable reuse and redistribution by users.

A textbook sales model that adds the cost of digital course content into students’ tuition and fees.