Chapter 1. Overcoming Family Opposition: The Battle to Get to College and Graduate School

Introduction

This chapter offers a brief glimpse into my academic and personal background and explains much of the rationale for the advice I give to students and their families. My goal is not to say there is one right answer or one right away to “do college” or that my way is right. It is simply my story. But my experiences, combined with almost daily conversations with students for just over 30 years, have convinced me that things must change for students to succeed and thrive in college.

While my advice is relevant for students regardless of their home life and personal situations, I am more concerned with the students who have been micro-managed by their high schools and families, and therefore lack many of the skills needed to solve problems on their own. I have found that it is often the “over-protected” students who struggle more, becoming anxious when small things go wrong and when their grades are not perfect. Some of the most resilient and adaptable students I know are those who struggled and worked hard to get to college, often with little to no support, especially first generation and/or low-income students. These students tend to be strong, determined, and used to figuring things out on their own because they have faced adversities throughout their lives. They have their own unique obstacles to face during their college years and schools need to offer more support for these students.

You now know a bit about why I chose to write this kind of book but, for additional context, I want to share some of my personal background. Specifically, how I got to college, how I made it to graduate school, and what happened for me in the world of work. As part of that journey, I will share some background on my parents’ story and how I was raised. If you watched the television series Ghost Whisperer, the opening credits include a line from the lead character who says, “In order for me to tell you my story, I have to tell you theirs.” I feel I need to tell you some of my story.

Words of Wisdom

Every student should be able to be responsible for selecting their own classes and picking their own major. A major does not always correlate with a career!

My upbringing plays a large role in why I feel so strongly about letting students who want to go to college do college on their own terms. This approach means letting students stumble, fail, get back up, and succeed or move on. It does not mean mapping out their classes, their major, or their activities. I am sharing some of my personal background in this chapter to demonstrate why I feel so strongly about parents or guardians (or any adult in charge of a minor) letting go when their young adult goes to college, why I feel so strongly that students must make their own path, and why I am such a strong advocate for students to find their own path. This advice absolutely does not mean that a child who goes to college should stop interacting with their parent, parents, or guardians. It suggests that the relationship should change. I often tell parents that they are no longer the coach; they are now the cheerleader. So, of course, stay involved, listen, advise, interact, but please let your child, or the college student you are responsible for, find their own way, solve their own problems, and create and own their college experience. The experience will be much more meaningful for them if you do. In this process, you may need to let them fail, recover, learn, and try again. When missteps happen, and they will because we all have failures in our lifetime, your child will rely on the coping skills that they developed.

Did I know what I would be doing today when I started college? No. Did I believe I would and could be an archaeologist? To be honest, I do not know. Maybe. But more importantly, I knew it was what I wanted to study. I wanted to know more. I had to know more. I wanted to immerse myself in an understanding of the past not only to understand the past for its own sake, but also to reflect on the present and the future. I was fascinated by the possibility of learning about the lives of people who lived decades, centuries, or millennia before us by studying what they left behind. This sentiment is an over-simplification of what archaeology is but, at the time (tenth grade), that was my inspiration.

All things being equal, I had a comfortable life growing up. I lived in a very nice home, I went to good schools, there was plenty of food and nice clothes, and I was (eventually) able to go to college. Growing up in Center City Philadelphia in the 1960s and 1970s was a bit odd. I had only a few neighborhood friends and by the time I started sixth grade, I had almost none; my friends were all living in the suburbs. In fact, I had several friends that were never allowed to stay at my house because it was in “the city.” This rule had nothing to do with me or with my parents; my friends’ parents did not want them to go into Center City Philadelphia. “She can always come here,” they would say, “but you cannot go stay there; she lives downtown—in the city.”

It took several years of therapy (on and off) and some reassuring comments from relatives and family friends to help me gain some insight into my childhood, and to help me understand that I grew up in an abusive household. Based on the stories I recounted, two different counselors confirmed for me that I was a victim of abuse (more recently a counselor was convinced I have post-traumatic stress disorder/PTSD). I remember asking one counselor why I had not confronted these memories until my early to mid-thirties. When my son was about two years old, I experienced panic attacks when my parents would say they were coming to visit me in Virginia. While it was never easy before, once my children were born it became harder. I became terrified of being alone with my parents, of what could or would happen when I was with them. When I asked my counselor, “Why now?”, she replied, “sometimes you don’t realize how bad the ship you’re on is until you get off and look behind.” In other words, as a new mother, I started to see parenting and my upbringing in a new light.

When my father died, the wife of one his closest friends told me, “We were always worried about you.” Comments like this one were validation of what I went through, and it meant a lot to me. When my mother passed away in 2016, my father’s sister told me that she knew how bad things were for me when I was growing up. She also acknowledged that my situation was much worse than my younger sister’s. She said she tried to help when she could, but there was only so much that she, or anyone else, could do.

My Family: A Brief Overview

Neither of my parents attended college, which made me a first-generation college student. While there is a huge push today to admit and graduate more first-generation college students, this term was not one I knew when I attended college or even when I first started working in higher education.

My mother graduated from high school and then attended the Fashion Institute of Technology in New York to become a dress designer. She worked for several labels in New York and then in Philadelphia after marrying my father. She was quite successful, though not famous. My father’s secondary education ended after the ninth grade. When my father was young, he was arrested three times for fighting and sent to court after the last incident. My grandmother told me that the judge gave him the choice of jail or trade school; my father said jail and she said trade school. My father replied, “Okay, I’ll be a plumber or an electrician.” In turn the judge said, “Those spots are full. We have one space open—in beauty school.” Again, my father replied, “Jail.” My grandmother issued the final word, “You’re going to beauty school.” At around age 16, he went to the Edward W. Bok Technical School in Philadelphia and became a hairdresser.

After his graduation from Bok, he joined the Marines and fought in some of the worst battles of World War II—Iwo Jima, Saipan, and Tinian. I grew up hearing about these places, though he mostly told “benign” stories; he never discussed the horrors of the war with me. He returned from the war with what we now would call PTSD. He did not want to work in his father’s junk shop which left him only one other choice—to find a job as a hairdresser.

He was incredibly successful at this profession. He met my mother in Paris at Maxim’s restaurant during Fashion Week, and they later married. She moved to Philadelphia where he opened his own salon, later merging with some other business owners to open numerous hair salons, a school, and a beauty supply company. He would help expand Intercoiffure Mondial, an international community of hairdressers focused on beauty and fashion, serving as its President from 1967 to 1975.

My father was an avid reader of fiction and non-fiction books and he read two newspapers a day. He traveled the world for business. However, he never came to value a formal college education and thus, when it was time for me to apply to college, he saw no need for me to attend. His plan was for me to go to work for him in his salon business. I had no interest in doing so; I had no sense of fashion, no business sense, and I was burned out by age 17 because I had worked for him in his salons since I was seven years old. All that mattered to him was what he wanted. A perfect formula for a very unhappy life for me.

By the time I applied to college, I knew I wanted to study archaeology and this only made my battle harder. Thanks to my father’s friends and business partners, I “won” the battle. I was able to go to college and major in archaeology. My father’s plan for me then switched a bit; I could attend college but after I graduated, I would go to work for him. I would spend the next four years, and more, trying to figure out an alternative plan and a way to break away.

My Early Years

I attended City Center Elementary School through the fifth grade; the school is now called Albert M. Greenfield Elementary School, a change that happened shortly after I left. Originally, the school was in the back of the YMCA on Chestnut Street between 20th and 21st Streets, about four blocks away from my house. After I moved on to the sixth grade, the city constructed a standalone building for the school located at 2200 Chestnut Street.

My parents were not too invested or interested in what I was doing in school. I earned decent grades, with most of my teachers commenting that I tended to talk with my friends too much. In the fifth grade, the idea of private school came up from both my aunt (my father’s sister) and my father’s business partner. The Philadelphia school system seemed to be declining, and they both believed I might be better off in a private school, specifically, a Jewish day school. There was only one option for public high school, Girl’s High School, and it was somewhat far from where we lived. My father wanted no part of me attending a private school. According to him, the city schools were acceptable, and he saw no reason to pay for school. I did not want to leave my current school until I learned two things about the private school: (1) you could wear anything you wanted to school, including pants, and (2) the teachers let you chew gum in class. I was 10 years old so clearly this new school was the right choice for me.

Discussions ensued and I took the entrance exam. I was nervous because by this time I wanted to go to the private school. My father remained firmly against it and my mother was silent on the issue, a trend that would continue through much of my life. Sometime in the spring, I learned that I had been accepted and by then my father’s family and friends had exerted enough pressure that he was willing to let me go.

In September 1965, I began attending my new school starting the sixth grade. It was a great school and almost all my memories from there are good ones. Home was a different story; school and my friends at school became my escape.

The school was approximately 30 to 40 minutes away from Center City in Lower Merion, just outside of Philadelphia. The school did not have school busses, so we all relied on rides (which was never an option for most of us), walking (for those who lived nearby), or public transportation (my option). The day before school started my mother made the trip to school with me. She showed me where to get the first bus, how to ask for a transfer, and then where to get off and walk to the second bus. She pointed out key landmarks for me to use to navigate. We took the 40-minute ride together, got off the bus and walked to school. Then we turned around and went back home. The next day she said goodbye to me, and I walked out the door, on my own, to get to school. I was 10 years old. Anyone who knows me knows that I am directionally challenged. Somehow that day, my first day in a new school, I found my way there and back.

The second bus I took went right up to my new school, just across the street. However, because it was in a different county or precinct, you needed a transfer pass that cost more money. This rule meant that commuters from Philadelphia and even New Jersey had to get off at the last stop before a transfer was needed. Children attending the school walked a mile to school from the last stop. None of our parents were willing to pay the extra fare for us to get dropped off across the street from the school. For most of us, the money was not the issue; our parents simply saw no reason for us not to walk. And so we did. Sometimes, when the weather was bad, pouring rain or inches of snow, the bus driver would wink and tell us to “just stay on the bus..” He would take us to the next stop, free of charge. That always made our day.

I attended my small private school for seven years through the 12th grade. I was in small classes and I had (mostly) good teachers. The class that had the most significant impact on me was my tenth grade Ancient History class; it is what resulted in my passion for archaeology. I was spellbound by the idea that you could learn about and interpret the past from materials that remained in the ground. You could, perhaps, learn about what people ate, how and where they lived, what they traded, and what tools they made and used for survival. The focus of the class was on the Old World and sites in the Middle East. While this area would not be the area of the world I would choose for my research, I was mesmerized and fascinated. A trip to Masada in Israel the following summer would lock in this interest. I loved this class, and the instructor was wonderful. I have tried to find him online to thank him and let him know the impact he had on my life, but, unfortunately, I have never been able to do so.

My Fight to Get to College

In early fall of my senior year, I did what many high school seniors do. I took the SAT test, followed by the SAT Subject II tests, and I started applying to colleges. I have no idea what the process looked like for most people, but it was far from an easy process in my house. My father originally refused to allow me to go to college, saying there was no way he would pay for it. His plan was that I would go to work for him and take over his business one day. I did not have the same vision. I cannot tell you exactly what I saw in my future when I was 17 years old, other than a passion for archaeology and ancient history, but it was definitely not spending the rest of my life running beauty salons.

With the support of my father’s business partner and his best friend from the Marine Corps, he finally allowed me to go to college. However, there were strings attached; I could only go to a local school where I could still live at home (not because of the cost but because he was controlling), and I had to major in business or education.

I remember the day I came home and announced that I knew what I wanted to study in college: archaeology. My father said something to the effect of, “I don’t know what the hell that is, but I’m not paying for it.” I went blank; it was a gut punch. I was devastated and I felt hopeless. I cried while I sat in my room and tried to figure out what I could do. The only alternative I could think of was to go to college, study business or education, graduate and get a job, earn money, and go back to study archaeology later. When I told him this plan, he clearly did not care and replied that he would not allow it because I would be working for him. I wanted to run away, but I was 17 years old and had no place to go. I spent many stressful hours thinking about what I could do. All I knew was I had to figure it out.

Again, I was saved by my father’s business partners and his best friend. I overheard arguments between them and my father as they tried to advocate for me. Adolf Biecker, his business partner, loved archaeology and was especially fascinated by the prehistory of Peru. We would talk about it for hours even though I knew very little other than what I learned from the few books I had read at his recommendation. I had a small glimmer of hope that he could help me, but it was weeks before my father budged. He finally said I could leave home and study what I wanted. I was elated; I had hope. Maybe I would get out.

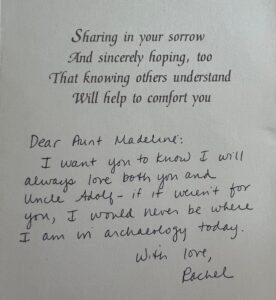

If I had any doubts about this memory, they were confirmed by a note I sent to Madeline Biecker, Adolf’s wife. I found this note after one of my parents died and I saved it. I wrote the note on a sympathy card I sent to her when Adolf passed away. I remember being so sad and I felt the loss deeply; they both had become family. The card was postmarked May 20, 1980.

By the time my father made his decision, it was early spring. I had applied only to local colleges, specifically Drexel University, Villanova University, Temple University, and the University of Pennsylvania. Drexel and Villanova did not offer archaeology at the time, but Temple and the University of Pennsylvania did. I was accepted to Temple, but not to the University of Pennsylvania. I found two additional schools with rolling admissions and archaeology programs—Boston University and Northeastern University. While I was admitted to both schools, when I looked at the cost and the programs, I decided that Temple University was the more logical choice as it would be less expensive and perhaps not anger my father as much.

Israel

A trip to Israel when I was 17 years old also became a turning point in my life. Somewhat planned and somewhat of a fluke, I lived on a kibbutz for close to four months, from February to June in 1972. My high school was private and somewhat progressive. It was clear to the school’s administration that once students were accepted to college (and almost everyone from my high school, though not all, went to college), most of them were not motivated to keep up with their classes and homework. The school therefore created a program called the Senior Work Study Project in which each student had to shadow an adult who worked in a profession that they hoped to pursue. Students shadowed doctors, lawyers, accountants, teachers, etc. I, along with two other friends who were also interested in archaeology, secured a place at the University of Pennsylvania’s Museum of Anthropology and Archaeology. Though still battling with my father about whether I could go to college, where I would live, and what I would study, this position was exactly what I wanted to do and a silver lining to the stormy home life during my senior year of high school.

Words of Wisdom

One of the pieces of advice I have given students is to have a plan, but be willing to veer away from it if something else comes along and your gut screams “Do it!”

Despite having what was my dream plan (working in an archaeology lab), one of my closest friends, Toby Dickman, proposed another idea. She wanted to go to Israel and live on a kibbutz and she did not want to go alone. While I was intrigued, I was not sure my school would approve it. “Of course they will approve it,” she told me, “They would never deny us a trip to Israel.” We proposed it, it was approved, and we found an organization in New York that matched students with a kibbutz where they could live and volunteer. We were assigned to Kibbutz Ma’anit, near Hadera, Israel. The mystery to me is why our parents agreed to let us go. I do not recall the details; maybe it was because it was Israel, or a job, or part of the high school experience. For me, perhaps, it may have been because my father preferred any alternative to my working in an archaeology lab for three to four months. Whatever their reasons, we were going to Israel to live and work on a kibbutz for almost four months.

Sometime in mid-February, my mother drove me and Toby to JFK airport and dropped us off. I had just turned 17 and Toby was 16 (she lied about her age so that she could go). We boarded a flight to Israel, via Frankfort, and landed at Lod Airport (now Ben Gurion International Airport) near Tel Aviv after some 18 hours of travel. No one met us, no one told us where to go or where to stay; there were no prior arrangements. We were not due at the kibbutz until the next day. We hailed a cab and asked the cab driver to take us to a hotel or a hostel (we were both fairly fluent in Hebrew). I am not sure where we went, but we were fairly convinced that it was a brothel. We called home, found some street food, and locked ourselves in our room, not sure we would make it to morning. It was loud and people were coming and going all night. People regularly knocked on our door. The next day we woke up and made our way to the bus station, dragging our large suitcases with us to get our tickets to the kibbutz. We probably could not have looked more like American tourists if we tried. We spoke the language, but we looked out of place, traveling alone and hauling our big suitcases. Though I used some incorrect words and ended up with the wrong tickets, we finally we got on the correct bus, still laughing at ourselves and feeling nervous. We told the bus driver our destination and asked him to let us know when we should get off the bus. After about 90 minutes, the bus pulled over and the driver told us that we had arrived. I imagined we would be dropped off at a building to check in and meet our hosts, but looking out the window all I saw was open fields. We were “in the middle of nowhere.”

We had no idea where to go. Luckily, a girl about our age named Hannah also got off the bus and she asked us if she could help. Again, we were so thankful that we could at least speak Hebrew and we told her we were going to Kibbutz Ma’anit. She replied that she lived there and showed us the way. As we hauled our luggage across the fields, we had no idea what to expect. We eventually made it to a main building where we checked in and were assigned to a room in a barracks-style building. We shared the room with one other girl. We were issued our work clothes, work assignments, and a meal schedule. All meals were held in the common dining hall. Our adventure was underway.

Because we could speak Hebrew, we were often assigned jobs that required an explanation or minimal training. Not much training or explanation was required to wash dishes, clean the childrens’ houses, or wash clothes. Working in the banana and apple fields required some training and so did caring for the chickens and cleaning their coops. As a result, we did almost every job a volunteer could do during our time there.

While we met many people who lived on the kibbutz, we also met people from all over the world. In the “backpack-through-Europe” days, navigating to a kibbutz in Israel became a popular thing to do, especially if you ran out of money. Though we earned the equivalent of about $1.00 US per week, we were housed, fed, and clothed. It was a good place to be if you had no place to go and no money. Our Kibbutz was also relatively affluent—it had a club house where we could watch television and a swimming pool where we spent a lot of our late afternoons after work. We stopped working early on Friday and had Saturday off so we could take a bus or hitchhike to the beach. Hitchhiking in Israel was a common method of transportation at the time and was relatively safe if you were not alone.

At the end of four months, we both called home to say we were going to stay in Israel and continue to work on the kibbutz. We were happy; we had Israeli boyfriends. These conversations did not go well for either of us; we were instructed by our parents that we must return home for our high school graduation before the third week of June (my father used more flowery language). We left the day before our graduation and arrived back in New York the morning of our high school graduation, feeling quite sad and jet lagged.

Why do I recount the details of this story? The time I spent in Israel impacted my life profoundly. I was 17 years old, meeting new people, speaking a different language, and finding my way socially and geographically. I was independent. I made amazing friends and stayed in touch with them for years. Toby was already a close friend and, since we went to the same college, Temple University, our bond only strengthened. I became more confident and able to stand up for myself (though still not to my father). When the Yom Kippur War broke out on October 6, 1973, I announced to my family that I was dropping out of school and moving to Israel to join the army. Suddenly an advocate for a college education, my father convinced me to finish the semester. After that, he said, I could go. The war ended quickly, and I stayed to finish college. However, his plan for me remained the same—I would go to work for him right after graduation.

College

I started college at Temple University in fall 1972. I was thrilled to finally be taking some anthropology and archaeology classes at the college level. Overall, my college experience was positive; I found it sometimes difficult, but invigorating. Since it had been such a battle to convince my parents, really my father, that I wanted to study archaeology, I could not believe I was enrolled and studying what I wanted to study. I was still living at home during my first year so it was hard to get immersed in college life. On the other hand, Temple University was largely a commuter school and I met other students in the same position. I took the bus or the subway each way; my friend Toby and I would occasionally commute together, just like in high school. We even had a few classes together. Things were going well; I was happy. I knew my father still expected me to take over his business when I graduated, but I had four years to develop my own plan.

In the spring, I enrolled in a Water Safety Instruction class to get re-certified as a lifeguard. This class choice was a turning point in that I met and made some dear friends who I am still in touch with today. A few people in the class were on the swim team and I was able to walk on to the team. I had not swam competitively for years so it was a challenge to get into shape. I also wanted desperately to move out of my house and into the dorms. That, of course, would be another battle.

Swimming was a huge part of my life since I was very young; it still is. I was born with dislocated hips and the doctors said swimming was the best therapy. My mother had never learned to swim and was terrified of the water so I had to wait until I could take lessons on my own, which was around the age of three. I loved it. It would soon become my escape, a place where I experienced a “runner’s high” except I was swimming. It was and has always been the one place where I can clear my brain. I get focused on counting laps and everything else goes away. On the Temple University swim team, I was far from the best swimmer, but I loved it. I still do.

But my father refused to let me leave. I made every argument I could think of: I wanted to be on the swim team and morning practice was at 6 AM; I wanted to study more and be able to take early morning classes; I wanted to meet more people. Again, his friends intervened and eventually I moved out of my house and into the dorms for my second and third years of college.

I remember moving in at the start of my second year and feeling both joyous and a little tearful, though I am not sure why. I had no doubts about leaving, but there was a small part of me that would miss some of the comforts of home, especially my room which served as my haven in the craziness. I think it took me less than one night to rid myself of any regrets and to enjoy the freedom I now had living on my own. I felt so lucky. I had escaped.

I was not completely free, however. Since I was only a few miles away, I was still on call for family dinners, business dinners, Saturday work at the salon, or attending Philadelphia Eagles football games. I avoided answering the phone and often claimed I was out studying or staying at a friend’s house. If I did answer, and if I was asked (or told) to do something, I usually found a reason to go back right after those things ended and, at the worst, I left early the next morning.

My second and third years of school were even better; I loved being away from home. I felt safer; I was safer. In the summer of 1974, after my second year, I enrolled in an archaeology field school at West Point, New York. I spent the summer doing field work and I loved it despite the hard, manual labor in the heat. It confirmed for me again that this work was what I wanted to do with my life.

In the summer of 1975, after my third year, a friend and I decided we wanted to find a field school out west. We applied to several programs and Arizona State University (ASU) had the best (and most affordable) one. Attending the ASU field school was another somewhat spur of the moment decision and another one that would change my life. We flew to Arizona and were met at the airport by Professor Ed Dittert, a leading scholar in Southwest archaeology. We drove north in his jeep to Payson, Arizona where we would spend the summer. I was immediately drawn to the desert landscape. We mostly conducted excavation work that summer, but I also spent time in the lab analyzing artifacts, completing archaeological survey work, and writing field reports and a paper.

It was a perfect summer and neither of us wanted to leave so we stayed. I took undergraduate classes at Arizona State University that would count toward my degree at Temple. I do not remember how I convinced my father; perhaps he thought this was only a temporary whim. I lived in an awful place, but I was happy. I finally learned to ride a bike at 20 years old. I took a part-time job making phone calls to sell carpet cleaning services so I would have some money. I swam (on my own) almost every day, which was still my mental therapy. I took an ecology class and three archaeology classes while I was there and I left, reluctantly, in December. I was set to graduate early now, and I wanted to keep working in archaeology. My father’s plan still called for me to work for him. Luckily, my credits did not transfer in time, so I returned to Temple to take more archaeology classes and to swim for one last semester.

Meanwhile, things were tense at home and I was miserable. I stayed away as much as I could, but it was hard. I also knew I had just a few months before my father thought I would start working for him.

In summer 1976, I got a job with a faculty member at Temple as a crew chief on a project in “exotic” Trenton, New Jersey. We were excavating a prehistoric site that would be flooded by modern construction. We all lived in a large house together. In the evenings, we worked cataloging artifacts and preparing for the next day.

Luck was on my side, again. I was offered a job for the summer working on an excavation in downtown Philadelphia. Interstate 95 was being expanded and there were several archaeological sites in the path. Since it was a paid job, my father agreed and I bought myself some more time, though the clock was ticking.

South Carolina

My unplanned gap year in South Carolina turned out to be another lucky choice and a pivotal year in my life in many ways. I did not know it at the time, nor did I plan it, but, in retrospect, I learned so much in that year, both personally and professionally. It is likely why I was successful in graduate school.

In 1976, I was set to start graduate school at Temple University, the same school where I earned my undergraduate degree. My memory is a bit vague on why I was even allowed to attend graduate school at Temple. It is possible I said I would work part-time, it was possible I said it was only a few years, and it was possible I never fully explained it. I had received funding so I was not asking for financial help so that may have played a part as well.

My father had insisted I move back home, but my friend invited me to live in an apartment with her outside of Philadelphia. I thought I could make it work financially and I enthusiastically said “yes.” Telling my father was another thing. At first, he seemed to be okay with the decision. I was 21 so I did not technically have to ask him, but I was still terrified of him. Then, one night shortly after I told him, my mother woke me up around 2:00 AM to tell me I had to go downstairs and talk to him because he was livid. I nervously went downstairs and into the kitchen where my father screamed at me for some amount of time. Thirty minutes? An hour? I was told I was ungrateful, useless, a disappointment. I was asked what was so wrong with our house that I would rather move out, pay rent, and live with a friend. It went on and on until I finally said I would not move out. I was devastated and terrified that I would never get out of my house. I called my friend the next day to tell her what happened and to tell her that I could not share an apartment with her when I started graduate school. Things were bad again; I needed to find a way out. I was headed for graduate school in a few weeks, and I was being forced to live at home again.

Later that summer, three friends and I decided to take a road trip across the country. I had worked doing archaeology all summer, which meant I was able to save some money. The reason for the trip was to attend a conference in Mexico, but it was our excuse for a road trip. That trip changed the course of my life again and put me on the path to freedom.

The four of us set out in a Volvo station wagon, stopping along the way at various places. As we headed into Arizona, I felt at peace. I had fallen in love with the landscape, the desert, and the archaeology of the American Southwest.

After the conference, we decided to travel the more southern route and stop in Atlanta to see the family of my friend Judy and then head to Columbia, South Carolina to see the professor who had directed our 1975 field school at Arizona State University. We were out of money by then, except for enough for gas, so we took turns sleeping and driving and drove straight through from Canyon de Chelly, New Mexico (our final stop in the Southwest) to Atlanta, Georgia before driving to Columbia.

While in Columbia, we each discussed our future plans, and I mentioned that I was starting graduate school at Temple University in a few weeks. Our former field director, Glen, replied, “You don’t want to do that.” When I asked why he explained that if I loved the American Southwest, then the program at Temple was not the right fit for me. I should be going to Arizona State University, the University of Arizona, or the University of New Mexico. Glen proposed a solution: “We have a one-year position open for a research assistant and it starts in a week or so. Are you interested?” With little idea of what I was getting into, I immediately said yes. The position was at the Institute of Archaeology and Anthropology at the University of South Carolina. He said they needed a female because all their other research assistants were male, and he would make some calls. I was hopeful, but I knew it was not guaranteed. I also knew this could be my way “out” of Philadelphia.

We headed home and I wondered what would happen. I still felt the need to get out and away. I did not think I could survive the demands of my father any longer. He was already telling me I needed to help at one of the salons until graduate classes started. A morning or two later, my mother woke me in the early morning to say that I had a phone call from someone in South Carolina. I tried to clear my voice and sound awake. I was offered the job—did I want it and, if so, could I get to Columbia in a few days? “Yes, and yes,” I replied. It was one the best decisions I have made; luckily, trusting my gut did not let me down.

I moved quickly. I called Temple University and told them I could not attend graduate school, apologizing profusely. I told my father I had been offered a job in South Carolina and that I wanted to take it. A job was something he understood, and he assumed I would be back home in a year. My mother offered to drive me there and some friends offered to let me stay with them until I found an apartment. I left. I was out. I was (somewhat) free.

Why was this year in South Carolina so critical in my life? It was a tough year for me personally as I was away from my friends, and I did not work with anyone my age or gender. Swimming once again became my therapy. I met another woman, a graduate student, who was swimming on the same schedule so we would meet at lunch or after work to swim. It was not until January of that year that I had any friends close to my age.

The year in South Carolina was critical to my future success in graduate school. I gained extensive field experience, guidance on which programs to apply to, and I read of archaeological theory. It was also a time of transformation for me; I learned to live alone, to manage being in a very different space and place, and I learned to learn. It was a year I could never have planned.

Arizona State University was my top choice for graduate schools. I had been there for a summer and a fall semester, and it was also far away from Philadelphia. When the call came that I was accepted, I said yes immediately. I did not know how I would pay for it, where I would live, or how I would get there, but I knew yes was the right answer.

I delayed telling my parents anything until very late spring. My father knew my job was ending so he assumed I would come home and be done with “whatever the hell it was I was doing”—his words. When I called to say proudly that I had been accepted to graduate school at Arizona State University, my father told me I could not go. Another gut punch, another battle. But I was slightly stronger now. I somehow managed to reply, “I’m not asking you; I am telling you that I am going.” I was not asking for help or money. I was going to make it work.

Graduate School

I left South Carolina in August 1977, to drive from Columbia to Tempe, Arizona in my 1972 Chevy Vega with a small trailer attached. I started classes in late August still in disbelief that I had made the move; I was in graduate school. My father was never supportive during this time, and he never bothered to try to understand what I was doing. He accused me constantly of acting like I was better than him with my “meaningless fancy college degrees.” I know I never acted that way. If someone were to ask him if he was proud of me, he would likely have said yes but those words were not something he ever randomly shared with me. But it was now 1977 and I was in Tempe, Arizona. A small part of me knew that my escape had begun and I was so happy.

Those years were wonderful and difficult. I was fully immersed in archaeology and I had wonderful friends and colleagues. I had the most amazing advisor, Dr. Sylvia Gaines, who would also become my friend, colleague, mother, and sister all rolled into one. I have modeled my career after her and I always told her how much I valued her.

The Moral of This Story

When I reflect on all of these experiences, I cannot help but think how incredibly lucky I was despite the problems along the way. The chances I took worked out. Each summer, when I spoke to the parents of new students, I told them that I truly cannot imagine my life had I not been able to study archaeology and make it all work. And each time, I get choked up when I say this. Every student entering college should have the opportunity to discover and pursue what they love. If I had been forced into another career, I would have been miserable, and likely failed out of school.

In summer 2021, during COVID, I was a guest lecturer in an online class filled with 60 incoming freshmen. I discussed the value of the liberal arts and the fact that your major is not your career. I provided some examples and gave a three-minute version of my story. After my lecture, I took a few questions and the first student said, “I love French. It is what I have always wanted to study, but my mother keeps telling me that I can’t have a useless major. I need to major is something useful like business.” When I get questions like this, they hit me hard; I feel the pain and angst of the students. I never have to think about my answer. “There is no useless major,” I said, “You should major in what you love and what you want to study. You get one chance to do this—do what you want, study what you love. The job will come regardless of your major.” She smiled. I hope she chose French.

Moving On

With this personal story as background, I move now to the second section of this book; what college is and should be, and why students should be encouraged to try, fail, and succeed. This section also includes a chapter devoted to the value of the liberal arts which seem to need constant defending. My opinions and ideas are based on my personal experiences, some of which are described above. They are also based on the literature, my years in graduate school working as an archaeologist in the field with undergraduates, my years of teaching college students, and my 30+ years as an academic dean (both an Assistant Dean and an Associate Dean) working with students, faculty, staff, and administrators.